Books / Introduction to Networking / Chapter 4

Internetworking Layer (IP)

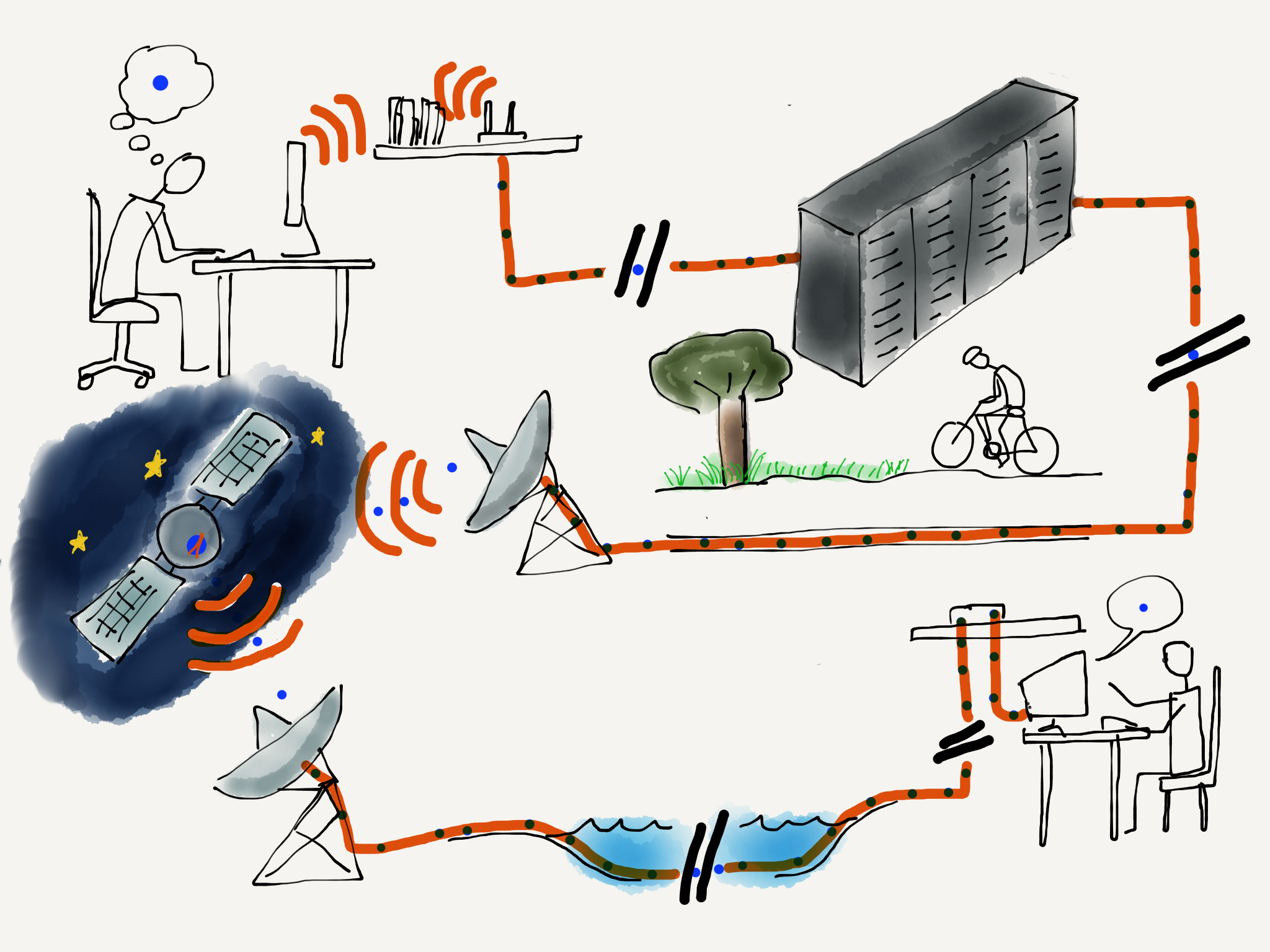

Now that we can move data across a single link, it’s time to figure out how to move it across the country or around the world. To send data from your computer to any of a billion destinations, the data needs to move across multiple hops and across multiple networks. When you travel from your home to a distant destination, you might walk from your home to a bus stop, take a train to the city, take another train to the airport, take a plane to a different airport, take a taxi into the city, then take a train to a smaller town, a bus to an even smaller town, and finally walk from the bus stop to your hotel. A packet also needs to take multiple forms of transportation to reach its destination. For a packet taking its “trip” to another country, the “walk”, “bus”, “train”, and “plane” can be thought of as different link layers like WiFi, Ethernet, fiber optic, and satellite.

Traveling Packets.

At each point during the trip, you (or your packet) are being transported using a shared medium. There might be hundreds of other people on the same bus, train, or plane, but your trip is different from that of every other traveller because of the decisions that you make at the end of each of your “hops”. For instance, when you arrive at a train station, you might get off one train, then walk through the station and select a particular outbound train to continue your journey. Travelers with different starting points and destinations make a different series of choices. All of the choices you make during your trip result in you following a series of links (or hops) along a route that takes you from your starting point to your destination.

As your packet travels from its starting point to its destination, it also passes through a number of “stations” where a decision is made as to which output link your packet will be forwarded on. For packets, we call these places “routers”. Like train stations, routers have many incoming and outgoing links. Some links may be fiber optic, others might be satellite, and still others might be wireless. The job of the router is to make sure packets move through the router and end up on the correct outbound link layer. A typical packet passes through from five to 20 routers as it moves from its source to its destination.

But unlike a train station where you need to look at displays to figure out the next train you need to take, the router looks at the destination address to decide which outbound link your packet needs to take. It is as if a train station employee met every single person getting off an inbound train, asked them where they were headed, and escorted them to their next train. If you were a packet, you would never have to look at another screen with a list of train departures and tracks!

The router is able to quickly determine the outbound link for your packet because every single packet is marked with its ultimate destination address. This is called the Internet Protocol Address, or IP Address for short. We carefully construct IP addresses to make the router’s job of forwarding packets as efficient as possible.

Internet Protocol (IP) Addresses

In the previous section where we talked about Link layer addresses, we said that link addresses were assigned when the hardware was manufactured and stayed the same throughout the life of a computer. We cannot use link layer addresses to route packets across multiple networks because there is no relationship between a link layer address and the location where that computer is connected to the network. With portable computers and cell phones moving constantly, the system would need to track each individual computer as it moved from one location to another. And with billions of computers on the network, using the link layer address to make routing decisions would be slow and inefficient.

The Internetwork Layer.

To make this easier, we assign another address to every computer based on where the computer is connected to the network. There are two different versions of IP addresses. The old (classic) IPv4 addresses consist of four numbers separated by dots like this, and look like this:

212.78.1.25

Each of the numbers can only be from 0 through 255. We have so many computers connected to the Internet now that we are running out of IPv4 addresses to assign to them. IPv6 address are longer and look like:

2001:0db8:85a3:0042:1000:8a2e:0370:7334

For this section we will focus on the classic IPv4 addresses, but all of the ideas apply equally to IPv4 and IPv6 addresses.

The most important thing about IP addresses is that they can be broken into two parts.^[There are many points where an IP address can be broken into “Network Number” and “Host Identifier” - for this example, we will just split the address in half.] The first part of the two-piece address is called the “Network Number”. If we break out an IPv4 address into two parts, we might find the following:

Network Number: 212.78

Host Identifier: 1.25

The idea is that many computers can be connected via a single connection to the Internet. An entire college campus, school, or business could connect using a single network number, or only a few network numbers. In the example above, 65,536 computers could be connected to the network using the network number of “212.78”. Since all of the computers appear to the rest of the Internet on a single connection, all packets with an IP address of:

212.78.*.*

can be routed to the same location.

By using this approach of a network number and a host identifier, routers no longer have to keep track of billions of individual computers. Instead, they need to keep track of perhaps a million or less different network numbers.

So when your packet arrives in a router and the router needs to decide which outbound link to send your packet to, the router does not have to look at the entire IP address. It only needs to look at the first part of the address to determine the best outbound link.

How Routers Determine the Routes

While the idea of the collapsing many IP addresses into a single network number greatly reduces the number of individual endpoints that a router must track to properly route packets, each router still needs a way to learn the path from itself to each of the network numbers it might encounter.

When a new core router is connected to the Internet, it does not know all the routes. It may know a few preconfigured routes, but to build a picture of how to route packets it must discover routes as it encounters packets. When a router encounters a packet that it does not already know how to route, it queries the routers that are its “neighbors”. The neighboring routers that know how to route the network number send their data back to the requesting router. Sometimes the neighboring routers need to ask their neighbors and so on until the route is actually found and sent back to the requesting router.

In the simplest case, a new core router can be connected to the Internet and slowly build a map of network numbers to outbound links so it can properly route packets based on the IP address for each incoming packet. We call this mapping of network numbers to outbound links the “routing table” for a particular router.

When the Internet is running normally, each router has a relatively complete routing table and rarely encounters a new network number. Once a router figures out the route to a new network number the first time it sees a packet destined for that network number, it does not need to rediscover the route for the network number unless something changes or goes wrong. This means that the router does a lookup on the first packet, but then it could route the next billion packets to that network number just by using the information it already has in its routing tables.

When Things Get Worse and Better

Sometimes the network has problems and a router must find a way to route data around the problems. A common problem is that one of the outbound links fails. Perhaps someone tripped over a wire and unplugged a fiber optic cable. At this point, the router has a bunch of network numbers that it wants to route out on a link that has failed. The recovery when a router loses an outbound link is surprisingly simple. The router discards all of the entries in its routing table that were being routed on that link. Then as more packets arrive for those network numbers, the router goes through the route discovery process again, this time asking all the neighboring routers except the ones that can no longer be contacted due to the broken link.

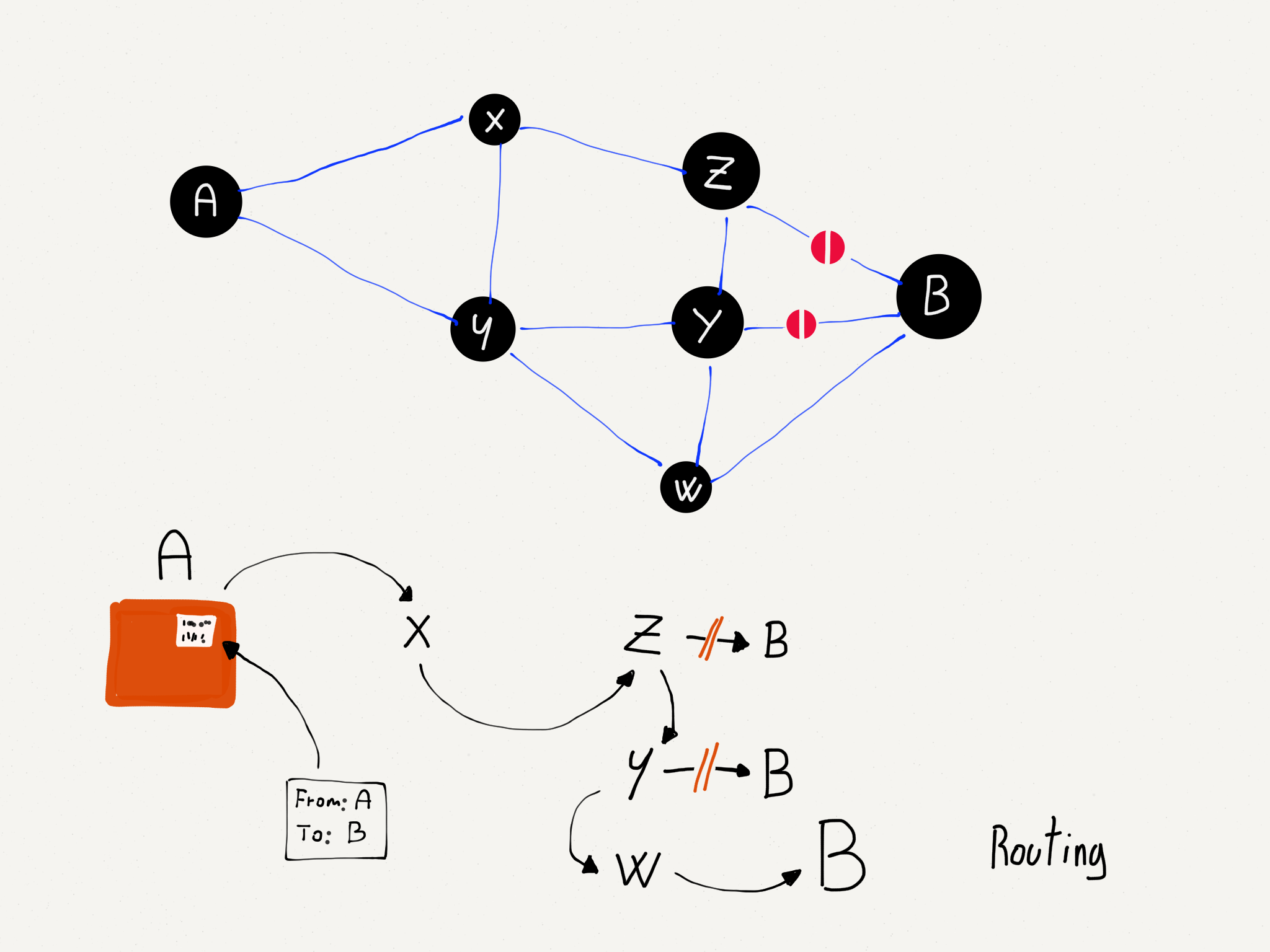

Dynamic Routing.

Packets are routed more slowly for a while as routing tables are rebuilt that reflect the new network configuration, but after a while things are humming along nicely.

This is why it is important for there to always be at least two independent paths from a source network to a destination network in the core of the network. If there are always at least two possible independent routes, we say that a network is a “two-connected network”. A two-connected network can recover from any single link outage. In places where there are a lot of network connections, like the east coast of the United States, the network could lose many links without ever becoming completely disconnected. But when you are at your home or school and have only one connection, if that connection goes down you are disconnected completely.

At some point the broken link is repaired or a new link is brought up, and the router wants to make best use of the new links. The router is always interested in improving its routing tables, and looks for opportunities to improve its routing tables in its spare time. When there is a lull in communication, a router will ask a neighboring router for all or part of its routing table. The router looks through the neighbor’s tables and if it looks like the other router has a better route to a particular network number, it updates its network table to forward packets for that network number through the link to the router that has a better route.

With these approaches to outages and the exchange of routing table information, routers can quickly react to network outages and reroute packets from links that are down or slow to links that are up and/or faster. All the while, each router is talking to its neighboring routers to find ways to improve its own routing table. Even though there is no central source of the “best route” from any source to any destination, the routers are good at knowing the fastest path from a source to a destination nearly all the time. Routers are also good at detecting and dynamically routing packets around links that are slow or temporarily overloaded.

One of the side effects of the way routers discover the structure of the network is that the route your packets take from the source to the destination can change over time. You can even send one packet immediately followed by another packet and because of how the packets are routed, the second packet might arrive at the destination before the first packet. We don’t ask the IP layer to worry about the order of the packets; it already has enough to worry about.

We pour our packets with source and destination IP addresses into the Internet much like we would send out a bunch of letters in the mail at the post office. The packets each find their way though the system and arrive at their destinations.

Determining Your Route

There is no place in the Internet that knows in advance the route your packets will take from your computer to a particular destination. Even the routers that participate in forwarding your packets across the Internet do not know the entire route your packet will take. They only know which link to send your packets to so they will get closer to their final destination.

But it turns out that most computers have a network diagnostic tool called “traceroute” (or “tracert”, depending on the operating system) that allows you to trace the route between your computer and a destination computer. Given that the route between any two computers can change from one packet to another, when we “trace” a route, it is only a “pretty good guess” as to the actual route packets will take.

The traceroute command does not actually “trace” your packet at all. It takes advantage of a feature in the IP network protocol that was designed to avoid packets becoming “trapped” in the network and never reaching their destination. Before we take a look at traceroute, let’s take a quick look at how a packet might get trapped in the network forever and how the IP protocol solves that problem.

Remember that the information in any single router is imperfect and is only an approximation of the best outbound link for a particular network number, and each router has no way of knowing what any other router will do. But what if we had three routers with routing table entries that formed an endless loop?

Routing Vortex.

Each of the routers thinks it knows the best outbound link for IP addresses that start with “212.78”. But somehow the routers are a little confused and their routing tables form a loop. If a packet with a prefix of “212.78” found its way into one of these routers, it would be routed around a circle of three links forever. There is no way out. As more packets arrived with the same prefix, they would just be added to the “infinite packet vortex”. Pretty soon the links would be full of traffic going round and round, the routers would fill up with packets waiting to be sent, and all three routers would crash. This problem is worse than having someone trip over a fiber optic cable, since it can cause several routers to crash.

To solve this problem, the Internet Protocol designers added a number to each packet that is called the Time To Live (TTL). This number starts out with a value of about 30. Each time an IP packet is forwarded down a link, the router subtracts 1 from the TTL value. So if the packet takes 15 hops to cross the Internet, it will emerge on the far end with a TTL of 15.

But now let’s look at how the TTL functions when there is a routing loop (or “packet vortex”) for a particular network number. Since the packet keeps getting forwarded around the loop, eventually the TTL reaches zero. And when the TTL reaches zero, the router assumes that something is wrong and throws the packet away. This approach ensures that routing loops do not bring whole areas of the network down.

So that is a pretty cool bit of network protocol engineering. To detect and recover from routing loops, we just put a number in, subtract 1 from that number on each link, and when the number goes to zero throw the packet away.

It also turns out that when the router throws a packet away, it usually sends back a courtesy notification, something like, “Sorry I had to throw your packet away.” The message includes the IP address of the router that threw the packet away.

Network loops are actually pretty rare, but we can use this notification that a packet was dropped to map the approximate route a packet takes through the network. The traceroute program sends packets in a tricky manner to get the routers that your packets pass through to send it back notifications. First, traceroute sends a packet with a TTL of 1. That packet gets to the first router and is discarded and your computer gets a notification from the first router. Then traceroute sends a packet with a TTL of 2. That packet makes it through the first router and is dropped by the second router, which sends you back a note about the discarded packet. Then traceroute sends a packet with a TTL of 3, and continues to increase the TTL until the packet makes it all the way to its destination.

With this approach, traceroute builds up an approximate path that your packets are taking across the network.

Traceroute from Michigan to Stanford.

It took 14 hops to get from Ann Arbor, Michigan to Palo Alto, California. The packets passed through Kansas, Texas, Los Angeles, and Oakland. This might not be the best route between the two cities if you were driving a car or taking a train, but on that day for packets between the two cities this was the best route on the Internet.

Notifications of Dropped Packets.

You can also see how long it took the packets to make it from the source to each router, and then from the source to the destination. A millisecond (ms) is a 1/1000 of a second. So 77.317 ms is just under a tenth of a second. This network is pretty fast.

Sometimes a traceroute can take a little while, up to a minute or two. Not all routers will give you the “I discarded your packet” message. In the example above, the router at hop 13 threw our packet away without saying “I am sorry”. Traceroute waits for the message and after a few seconds just gives up and increases the TTL value so it gets past the rude router.

If you run a traceroute for a connection that includes an undersea cable, you can see how fast data moves under the sea. Here is a traceroute between the University of Michigan and Peking University in China.

Traceroute from Michigan to Peking University.

You can see when the packet is encountering a long undersea cable in steps seven and eight. The time goes from less than 1/10 of a second to nearly 1/4 of a second. Even though 1/4 of a second is slower than 1/10 a second, it is pretty impressive when you consider that the packet is going nearly all of the way around the world in that 1/4 second.

The core of our IP network is remarkable. Most of the time we don’t really care how hard the routers are working to make sure our packets move quickly from our computer to the various destinations around the world. Next we will move from looking at how the core of the network functions to how IP addresses are managed at the edges.

Getting an IP Address

Increasingly, computers are portable or mobile. We just pointed out how important it was for the IP layer to track large groups of computers using network numbers instead of tracking every single computer individually. But since these network numbers indicate a particular physical connection to the network, when we move a computer from one location to another, it will need a new IP address. Remember that the link layer address is set when a computer is manufactured and never changes throughout the life of the computer. If you close your laptop in one coffee shop and reopen it using your home WiFi, your computer will need a different IP address.

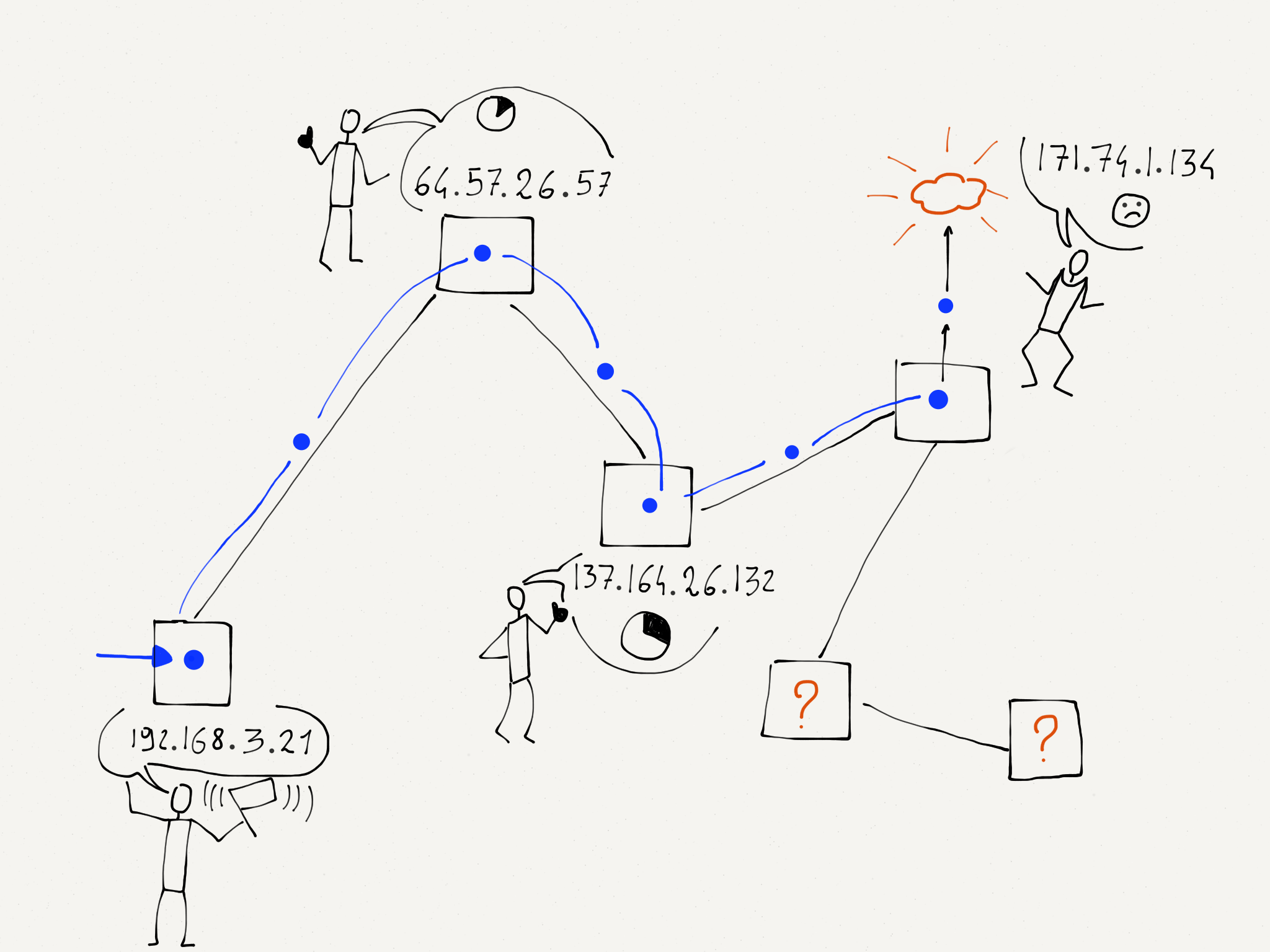

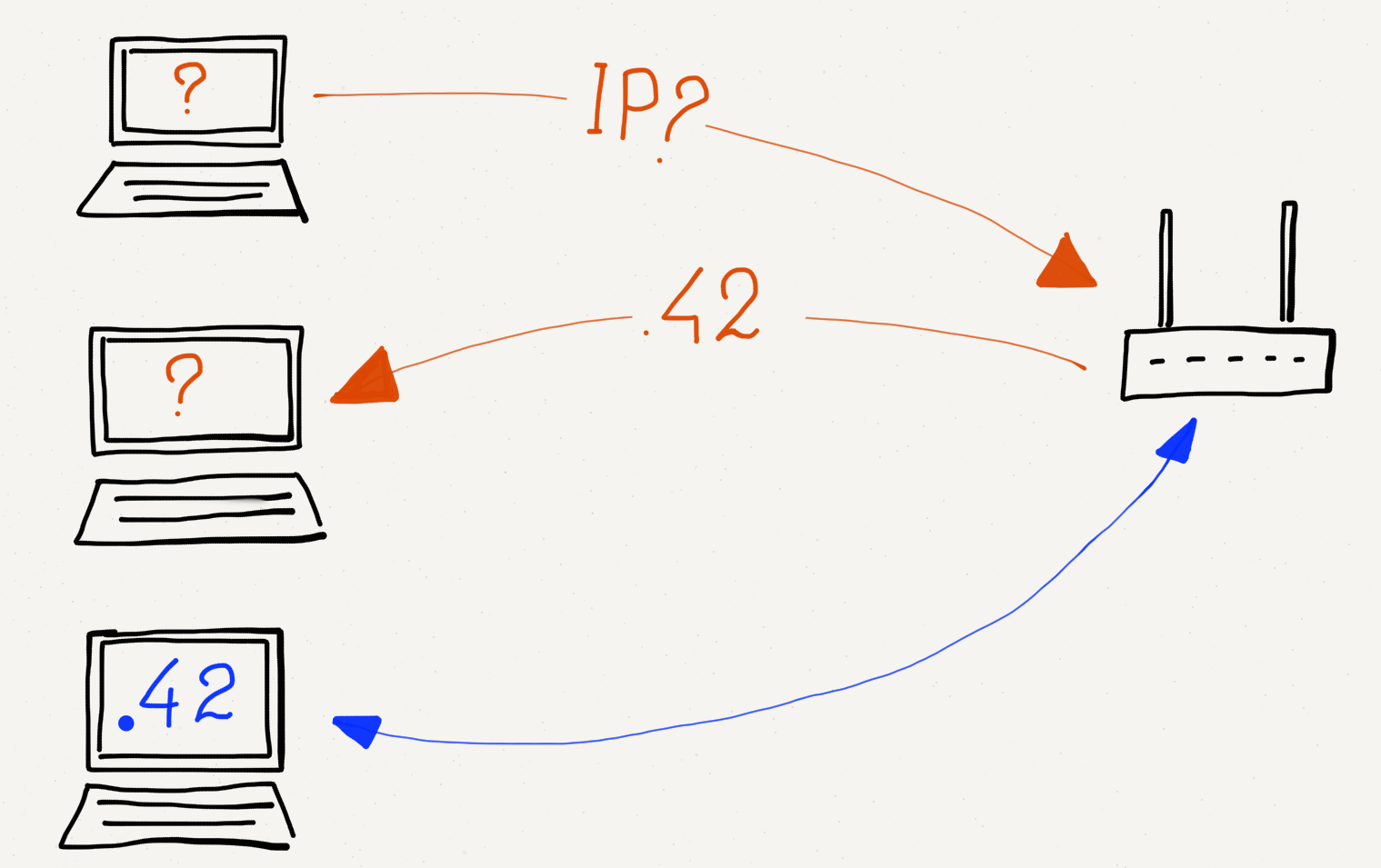

This ability for your computer to get a different IP address when it is moved from one network to another uses a protocol called “Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol” (or DHCP for short). DHCP is pretty simple. Going back to the Link layer section, recall the first thing your computer does at the link level is ask “Is there a base station on this network?” by sending a message to a special broadcast address. Once your computer is successfully connected at the link layer through that base station, it sends another broadcast message, this time asking “Is there a gateway connected to this network that can get me to the Internet? If there is, tell me your IP address and tell me what IP address I should use on this network”.

When the gateway router replies, your computer is given a temporary IP address to use on that network (for instance, while you are at the coffee shop). After the router has not heard from your computer for a while, it decides you are gone and loans the IP address to another computer.

If this process of reusing a loaned IP address goes wrong, two computers end up on the same network with the same IP address. Perhaps you have seen a message on your computer to the effect of, “Another computer is using 192.168.0.5, we have stopped using this address”. Your computer sees another computer with a link address other than its own using the IP address that your computer thinks is assigned to it.

Getting an IP Address via DHCP.

But most of the time this dynamic IP address assignment (DHCP) works perfectly. You open your laptop and in a few seconds you are connected and can use the Internet. Then you close your laptop and go to a different location and are given a different IP address to use at that location.

In some operating systems, when a computer connects to a network, issues a DHCP request, and receives no answer, it decides to assign itself an IP address anyway. Often these self-assigned addresses start with “169….”. When your computer has one of these self-assigned IP addresses, it thinks it is connected to a network and has an IP address, but without a gateway, it has no possibility of getting packets routed across the local network and onto the Internet. The best that can be done is that a few computers can connect to a local network, find each other, and play a networked game. There is not much else that can be done with these self-assigned IP addresses.

A Different Kind of Address Reuse

If you know how to find the IP address on your laptop, you can do a little experiment and look at the different IP addresses you get at different locations. If you made a list of the different addresses you received at the different locations, you might find that many of the locations give out addresses with a prefix of “192.168.”. This seems to be a violation of the rule that the network number (IP address prefix) is tied to the place where the computer is connected to the Internet, but a different rule applies to addresses that start with “192.168.” (The prefix “10.” is also special).

Addresses that start with “192.168.” are called “non-routable” addresses. This means that they will never be used as real addresses that will route data across the core of the network. They can be used within a single local network, but not used on the global network.

So then how is it that your computer gets an address like “192.168.0.5” on your home network and it works perfectly well on the overall Internet? This is because your home router/gateway/base station is doing something we call “Network Address Translation”, or “NAT”. The gateway has a single routable IP address that it is sharing across multiple workstations that are connected to the gateway. Your computer uses its non-routable address like “192.168.0.5” to send its packets, but as the packets move across the gateway, the gateway replaces the address with its actual routable address. When packets come back to your workstation, the router puts your workstation’s non-routable address back into the returning packets.

This approach allows us to conserve the real routable addresses and use the same non-routable addresses over and over for workstations that move from one network to another.

Global IP Address Allocation

If you wanted to connect the network for a new organization to the Internet you would need to contact an Internet Service Provider and make a connection. Your ISP would give you a range of IP addresses (i.e., one or more network numbers) that you could allocate to the computers attached to your network. The ISP assigns you network numbers by giving you a portion of the network numbers they received from a higher-level Internet Service Provider.

At the top level of IP address allocations are five Regional Internet Registries (RIRs). Each of the five registries allocates IP addresses for a major geographic area. Between the five registries, every location in the world can be allocated a network number. The five registries are North America (ARIN), South and Central America (LACNIC), Europe (RIPE NCC), Asia-Pacific (APNIC) and Africa (AFRNIC).

When the classic IPv4 addresses like “212.78.1.25” were invented, only a few thousand computers were connected to the Internet. We never imagined then that someday we would have a billion computers on the Internet. But today with the expansion of the Internet and the “Internet of things” where smart cars, refrigerators, thermostats, and even lights will need IP addresses, we need to connect far more than a billion computers to the Internet. To make it possible to connect all these new computers to the Internet, engineers have designed a new generation of the Internet Protocol called “IPv6”. The 128-bit IPv6 addresses are much longer than the 32-bit IPv4 addresses.

The Regional Internet Registries (RIRs) are leading the transition from IPv4 to IPv6. The transition from IPv4 to IPv6 will take many years. During that time, both IPv4 and IPv6 must work seamlessly together.

Summary

The Internetworking Protocol layer extends our network from a single hop (Link layer) to a series of hops that result in packets quickly and efficiently being routed from your computer to a destination IP address and back to your computer. The IP layer is designed to react and route around network outages and maintain near-ideal routing paths for packets moving between billions of computers without any kind of central routing clearinghouse. Each router learns its position within the overall network, and by cooperating with its neighboring routers helps move packets effectively across the Internet.

The IP layer is not 100% reliable. Packets can be lost due to momentary outages or because the network is momentarily “confused” about the path that a packet needs to take across the network. Packets that your system sends later can find a quicker route through the network and arrive before packets that your system sent earlier.

It might seem tempting to design the IP layer so that it never loses packets and insures that packets arrive in order, but this would make it nearly impossible for the IP layer to handle the extreme complexities involved in connecting so many systems.

So instead of asking too much of the IP layer, we leave the problem of packet loss and packets that arrive out of order to our next layer up, the Transport layer.

Glossary

core router: A router that is forwarding traffic within the core of the Internet.

DHCP: Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol. DHCP is how a portable computer gets an IP address when it is moved to a new location.

edge router: A router which provides a connection between a local network and the Internet. Equivalent to “gateway”.

Host Identifier: The portion of an IP address that is used to identify a computer within a local area network.

IP Address: A globally assigned address that is assigned to a computer so that it can communicate with other computers that have IP addresses and are connected to the Internet. To simplify routing in the core of the Internet IP addresses are broken into Network Numbers and Host Identifiers. An example IP address might be “212.78.1.25”.

NAT: Network Address Translation. This technique allows a single global IP address to be shared by many computers on a single local area network.

Network Number: The portion of an IP address that is used to identify which local network the computer is connected to.

packet vortex: An error situation where a packet gets into an infinite loop because of errors in routing tables.

RIR: Regional Internet Registry. The five RIRs roughly correspond to the continents of the world and allocate IP address for the major geographical areas of the world.

routing tables: Information maintained by each router that keeps track of which outbound link should be used for each network number.

Time To Live (TTL): A number that is stored in every packet that is reduced by one as the packet passes through each router. When the TTL reaches zero, the packet is discarded.

traceroute: A command that is available on many Linux/UNIX systems that attempts to map the path taken by a packet as it moves from its source to its destination. May be called “tracert” on Windows systems.

two-connected network: A situation where there is at least two possible paths between any pair of nodes in a network. A two-connected network can lose any single link without losing overall connectivity.

Questions

- What is the goal of the Internetworking layer?

- a)Move packets across multiple hops from a source to destination computer

- b)Move packets across a single physical connection

- c)Deal with web server failover

- d)Deal with encryption of sensitive data

- How many different physical links does a typical packet cross from

its source to its destination on the Internet?

- a)1

- b)4

- c)15

- d)255

- Which of these is an IP address?

- a)0f:2a:b3:1f:b3:1a

- b)192.168.3.14

- c)www.khanacademy.com

- d)@drchuck

- Why is it necessary to move from IPv4 to IPv6?

- a)Because IPv6 has smaller routing tables

- b)Because IPv6 reduces the number of hops a packet must go across

- c)Because we are running out of IPv4 addresses

- d)Because IPv6 addresses are chosen by network hardware manufacturers

- What is a network number?

- a)A group of IP addresses with the same prefix

- b)The GPS coordinates of a particular LAN

- c)The number of hops it takes for a packet to cross the network

- d)The overall delay packets experience crossing the network

- How many computers can have addresses within network number “218.78”?

- a)650

- b)6500

- c)65000

- d)650000

- How do routers determine the path taken by a packet across the Internet?

- a)The routes are controlled by the IRG (Internet Routing Group)

- b)Each router looks at a packet and forwards it based on its best guess as to the correct outbound link

- c)Each router sends all packets on every outbound link (flooding algorithm)

- d)Each router holds on to a packet until a packet comes in from the destination computer

- What is a routing table?

- a)A list of IP addresses mapped to link addresses

- b)A list of IP addresses mapped to GPS coordinates

- c)A list of network numbers mapped to GPS coordinates

- d)A list of network numbers mapped to outbound links from the router

- How does a newly connected router fill its routing tables?

- a)By consulting the IANA (Internet Assigned Numbers Authority)

- b)By downloading the routing RFC (Request for Comments)

- c)By contacting the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF)

- d)By asking neighboring routers how they route packets

- What does a router do when a physical link goes down?

- a)Throws away all of the routing table entries for that link

- b)Consults the Internet Map (IMAP) service

- c)Does a Domain Name (DNS) looking for the IP address

- d)Sends all the packets for that link back to the source computer

- Why is it good to have at least a “two-connected” network?

- a)Because routing tables are much smaller

- b)Because it removes the need for network numbers

- c)Because it supports more IPv4 addresses

- d)Because it continues to function even when a single link goes down

- Do all packets from a message take the same route across the Internet?

- a)Yes

- b)No

- How do routers discover new routes and improve their routing tables?

- a)Each day at midnight they download a new Internet map from IMAP

- b)They periodically ask neighboring routers for their network tables

- c)They randomly discard packets to trigger error-correction code within the Internet

- d)They are given transmission speed data by destination computers

- What is the purpose of the “Time to Live” field in a packet?

- a)To make sure that packets do not end up in an “infinite loop”

- b)To track how many minutes it takes for a packet to get through the network

- c)To maintain a mapping between network numbers and GPS coordinates

- d)To tell the router the correct output link for a particular packet

- How does the “traceroute” command work?

- a)It sends a series of packets with low TTL values so it can get a picture of where the packets get dropped

- b)It loads a network route from the Internet Map (IMAP)

- c)It contacts a Domain Name Server to get the route for a particular network number

- d)It asks routers to append route information to a packet as it is routed from source to destination

- About how long does it take for a packet to cross the Pacific Ocean

via an undersea fiber optic cable?

- a)0.0025 Seconds

- b)0.025 Seconds

- c)0.250 Seconds

- d)2.5 Seconds

- On a WiFi network, how does a computer get an Internetworking (IP) address?

- a)Using the DHCP protocol

- b)Using the DNS protocol

- c)Using the HTTP protocol

- d)Using the IMAP protocol

- What is Network Address Translation (NAT)?

- a)It looks up the IP address associated with text names like “www.dr-chuck.com”

- b)It allows IPv6 traffic to go across IPv4 networks

- c)It looks up the best outbound link for a particular router and network number

- d)It reuses special network numbers like “192.168” across multiple network gateways at multiple locations

- How are IP addresses and network numbers managed globally?

- a)There are five top-level registries that manage network numbers in five geographic areas

- b)IP addresses are assigned worldwide randomly in a lottery

- c)IP addresses are assigned by network equipment manufacturers

- d)IP addresses are based on GPS coordinates

- How much larger are IPv6 addresses than IPv4 addresses?

- a)They are the same size

- b)IPv6 addresses are 50% larger than IPv4 addresses

- c)IPv6 addresses are twice as large as IPv4 addresses

- d)IPv6 addresses are 10 times larger than IPv4 addresses

- What does it mean when your computer receives an IP address that starts with “169..”?

- a)Your connection to the Internet supports the Multicast protocol

- b)The gateway is mapping your local address to a global address using NAT

- c)There was no gateway available to forward your packets to the Internet

- d)The gateway for this network is a low-speed gateway with a small window size

- If you were starting an Internet Service Provider in Poland, which Regional Internet Registry (RIR) would assign you a block of IP addresses.

- a)ARIN

- b)LACNIC

- c)RIPE NCC

- d)APNIC e) AFRNIC f) United Nations