Books / Tkinter Tutorial for Beginners / Chapter 1

Getting Started

Tkinter is a wrapper around a GUI toolkit called Tk. It’s usually used through a language called Tcl, but tkinter allows us to use Tcl and Tk through Python. This means that we can use Tcl’s libraries like Tk with Python without writing any Tcl code.

Installing tkinter

If you installed Python yourself you already have tkinter. If you are using Linux you probably don’t, but you can install tkinter with your distribution’s package manager. For example, you can use this command on Debian-based distributions, like Ubuntu and Mint:

sudo apt install python3-tk

Hello World!

That’s enough talking. Let’s do the classic Hello World program :)

import tkinter

root = tkinter.Tk()

label = tkinter.Label(root, text="Hello World!")

label.pack()

root.mainloop()

Run this program like any other program. It should display a tiny window

with the text Hello World! in it. I’m way too lazy to take

screenshots, so here’s some ASCII art:

,------------------.

| tk | _ | o | X |

|------------------|

| Hello World! |

`------------------'

There are many things going on in this short code. Let’s go through it line by line.

import tkinter

Many other tkinter tutorials use from tkinter import * instead, and then they

use things like Label instead of tk.Label. Don’t use star imports. It

will confuse you and other people. You can’t be sure about where Label comes

from if the file is many lines long, but many tools that process code

automatically will also be confused. Overall, star imports are evil.

Some people like to do import tkinter as tk and then use tk.Label instead

of tkinter.Label. There’s nothing wrong with that, and you can do that too if

you want to. It’s also possible to do from tkinter import Tk, Label, Button,

which feels a little bit like a star import to me, but it’s definitely not as

bad as a star import.

root = tkinter.Tk()

The root window is the main window of our program. In this case, it’s the only window that our program creates. Tkinter starts Tcl when you create the root window.

label = tkinter.Label(root, text="Hello World!")

Like most other GUI toolkits, Tk uses widgets. A widget is something that we see on the screen. Our program has two widgets. The root window is a widget, and this label is a widget. A label is a widget that just displays text.

Note that most widgets take a parent widget as the first argument.

When we do tk.Label(root), the root window becomes the parent so the

label will be displayed in the root window.

label.pack()

This adds the label into the root window so we can see it.

Instead of using a label variable, you can also do this:

tkinter.Label(root, text="Hello World!").pack()

But don’t do this:

label = tkinter.Label(root, text="Hello World!").pack() # this is probably a mistake

Look carefully, the above code creates a label, packs it, and then sets a

label variable to whatever the .pack() returns. That is not same as the

label widget. It is None because most functions return None when they don’t

need to return anything more meaningful.

Anyway… let’s continue going through the lines of our example code.

root.mainloop()

The code before this takes usually just a fraction of a second to run, but this line of code runs until we close the window. It’s usually something between a few seconds and a few hours.

Hello Ttk!

There is a Tcl library called Ttk, short for “themed tk”. I’ll show you why you should use it instead of the non-Ttk code soon.

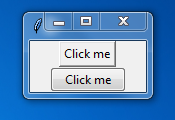

The tkinter.ttk module contains things for using Ttk with Python. Here is a

tkinter program that displays two buttons that do nothing when they are

clicked. One of the buttons is a Ttk button and the other isn’t.

import tkinter

from tkinter import ttk

root = tkinter.Tk()

tkinter.Button(root, text="Click me").pack()

ttk.Button(root, text="Click me").pack()

root.mainloop()

The GUI looks like this on Windows 7:

The ttk button is the one that looks a lot better. Tk itself is very old, and its button widget is probably just as old, and it looks very old too. Ttk widgets look much better in general, and you should always use Ttk widgets. tl;dr: Use ttk.

If you already have some code that doesn’t use Ttk widgets, you just need to

add from tkinter import ttk and then replace tkinter.SomeWidget with

ttk.SomeWidget everywhere. Most things will work just fine.

Unfortunately writing Ttk code is kind of inconvenient because there’s no way to create a root window that uses Ttk. Some people just create a Tk root window and add things to that, e.g. like this:

import tkinter

from tkinter import ttk

root = tkinter.Tk()

ttk.Label(root, text="Hello!").pack()

ttk.Button(root, text="Click me").pack()

root.mainloop()

GUIs like this look horrible on my Linux system.

<xqb> woa it sak balz :|

The background of this root window is not using Ttk, so it has very different

colors than the Ttk widgets. We can fix that by adding a big Ttk frame to the

Tk root window. A frame is an empty widget, and we can add any other widgets we

want inside a frame. If we add a ttk.Frame to the root window and pack it

with fill='both', expand=True, it will always fill the entire window, making

the window look like a Ttk widget. I’ll do this in all examples from now on.

root = tkinter.Tk()

big_frame = ttk.Frame(root)

big_frame.pack(fill='both', expand=True)

# now add all widgets to big_frame instead of root

This is annoying, but keep in mind that you only need to do this once for each window; in a big project you typically have many widgets inside each window, and this extra boilerplate doesn’t annoy that much after all.

Here is a complete hello world program. It shouldn’t look too horrible on anyone’s system.

import tkinter

from tkinter import ttk

root = tkinter.Tk()

big_frame = ttk.Frame(root)

big_frame.pack(fill='both', expand=True)

label = ttk.Label(big_frame, text="Hello World!")

label.pack()

root.mainloop()

Tkinter and the >>> prompt

The >>> prompt is a great way to experiment with things. You can also

experiment with tkinter on the >>> prompt, but unfortunately it

doesn’t work that well on all platforms. Everything works great on

Linux, but on Windows the root window is unresponsive when

root.mainloop() is not running.

Try the hello world example on the >>> prompt, just type it there line

by line. It’s really cool to see the widgets appearing on the screen as

you type. If this works on your system, that’s great! If not,

you can run root.update() regularly to make it display your changes.

Print issues

If you try to print a tkinter widget, the results can be surprising.

>>> print(label)

.!label

Doing the same thing looks roughly like this on Python 3.5 and older:

>>> print(label)

.3071874380

Here .!label and .3071874380 were Tcl’s variable names. Converting a

widget to a string like str(widget) gives us the widget’s Tcl variable

name, and print converts everything to strings using str().

>>> label

<tkinter.Label object at 0xb72aa96c>

>>> str(label)

'.3073026412'

>>> print(label) # same as print(str(label))

.3073026412

So if you’re trying to print a variable and you get something like

.!label or .3071874380, it’s probably a tkinter widget. You can also

check that with print(repr(something)), it does the same thing as

looking at the widget on the >>> prompt:

>>> print(repr(label))

<tkinter.Label object at 0xb72aa96c>

Widget options

When we created a label like label = tk.Label(root, text="Hello World!"),

we got a label that displayed the text “Hello World!”. Here text was

an option, and its value was "Hello World!".

We can also change the text after creating the label in a few different ways (we’ll find this useful later):

>>> label['text'] = "New text" # it behaves like a dict

>>> label.config(text="New text") # this does the same thing

>>> label.configure(text="New text") # this does the same thing too

The config and configure methods do the same thing, only their names

are different.

It’s also possible to get the text after setting it:

>>> label['text'] # again, it behaves like a dict

'New text'

>>> label.cget('text') # or you can use a method instead

'New text'

There are multiple different ways to do the same things, and you can mix them however you want. Personally I like to use initialization arguments and treat the widget as a dict, but you can do whatever you want.

You can also convert the label to a dict to see all of the options and their values:

>>> dict(label)

{'padx': <pixel object: '1'>, 'pady': <pixel object: '1'>, 'borderwidth': <pixe

l object: '1'>, 'cursor': '', 'state': 'normal', 'image': '', 'bd': <pixel obje

ct: '1'>, 'font': 'TkDefaultFont', 'justify': 'center', 'height': 0, 'highlight

color': '#ffffff', 'wraplength': <pixel object: '0'>, 'activebackground': '#ece

cec', 'foreground': '#ffffff', 'anchor': 'center', 'bitmap': '', 'fg': '#ffffff

', 'compound': 'none', 'textvariable': '', 'underline': -1, 'background': '#3b3

b3e', 'width': 0, 'highlightbackground': '#3b3b3e', 'relief': 'flat', 'bg': '#3

b3b3e', 'text': '', 'highlightthickness': <pixel object: '0'>, 'takefocus': '0'

, 'disabledforeground': '#a3a3a3', 'activeforeground': '#000000'}

That’s a mess! Let’s use pprint.pprint:

>>> import pprint

>>> pprint.pprint(dict(label))

{'activebackground': '#ececec',

'activeforeground': '#000000',

'anchor': 'center',

'background': '#3b3b3e',

...

If you are wondering what an option does you can just try it and see, or you can read the manual page (see below).

Manual pages

Tkinter is not documented very well, but there are many good manual pages about Tk written for Tcl users. Tcl and Python are two different languages, but Tk’s manual pages are easy to apply to tkinter code. You’ll find the manual pages useful later in this tutorial.

This tutorial contains links to the manual pages, like this ttk_label(3tk) link. There’s also a list of the manual pages.

If you are using Linux and you want to read the manual pages on a terminal, you can also install Tk’s manual pages using your package manager. For example, you can use this command on Debian-based distributions:

sudo apt install tk-doc

Then you can read the manual pages like this:

man ttk_label

Summary

- Tkinter is an easy way to write cross-platform GUIs.

- Now you should have tkinter installed and you should know how to use

it on the

>>>prompt. - Don’t use star imports.

- Now you should know what a widget is.

- Use ttk widgets with

from tkinter import ttk, and always create a bigttk.Framepacked withfill='both', expand=Trueinto each root window. - You can set the values of Tk’s options when creating widgets like

label = tk.Label(root, text="hello"), and you can change them later using any of these ways:label['text'] = "new text" label.config(text="new text") label.configure(text="new text") - You can get the current values of options like this:

print(label['text']) print(label.cget('text')) - If

print(something)prints something weird, tryprint(repr(something)). - You can view all options and their values like

pprint.pprint(dict(some_widget)). The options are explained in the manual pages.