Code coverage is a valuable metric. Software developers write tests for the code they have written and run code coverage analysis which gives them an assessment of how much of their code is covered by tests or more importantly what parts of the code are untested.

Some organizations and managers make high level of code coverage mandatory for their teams. “90% code coverage and no less!”, says the manager. It becomes another metric in management’s arsenal to assess code quality and (god forbid) team’s performance. It’s a big mistake to interpret and use code coverage in this way. Code coverage doesn’t say anything about the quality of the code or the tests. It is very easy to get high code coverage with low quality testing. Code coverage number will not say that some parameter was not checked for null value, that the contract required Strings to be trim()ed before use or that even though all lines of code were hit, some particular sequence wasn’t tested. Nope. The tests might be meaningless and brittle masking real issues, but who cares, as long as there is coverage.

Let me get this straight again: code coverage is a valuable metric. But when management turns it into a goal and becomes fixated on it to measure quality and performance, things rapidly disintegrate. It might have to do with our psychology or our nature, but we humans optimize our performance according to how we are being measured and become distracted from what really matters. Testing requires thoughtfulness and careful design. Scott Bain, author at Sustainable Test Driven Development explained it better:

If developers are writing unit tests because “the boss says so” then they have no real professional or personal motivation driving the activity. They’re doing it because they have to, not because they want to. Thus, they will put in whatever effort they have to in order to increase their code coverage to the required level and not one bit more. It becomes a “tedious thing I have to do to before I can check in my code, period.”

In his excellent article “How to Misuse Code Coverage”, Brian Marick discovered the same thing. Organization that mandated a code coverage percentage got just the percentage they wanted. Which is scary because it might be a sign that people are gaming the system to meet the target.

Perhaps this might hint at the answer: when I talk about coverage to organizations that use 85%, say, as a shipping gate, I sometimes ask how many people have gotten substantially higher, perhaps 90%. There’s usually a few who have, but everyone else is clustered right around 85%. Are we to believe that those other people just happened to hit 85% and were unable to find any other tests worth writing? Or did they write a first set of tests, take their coverage results, bang away at the program until they got just over 85%, and then heave a sigh of relief at having finished a not-very-fun job?

Even if we take the positive outlook that people will make an honest effort to meet enforced code coverage percentage, it’s still counter-productive to have them obsess over the code coverage as a number rather than focusing on the quality, sufficiency and maintainability of tests.

“But my team has had several bugs escape to production!”

Mandating a code coverage number is not the answer. If anything, you’ll make matters worse. Writing good tests is a skill. As a manager, it is your job is to figure out exactly what is going wrong.

I managed a team that consistently had issues with bugs. Luckily, we were catching these bugs in Q/A but because the development team was offshore and in a different timezone, the feedback loop was becoming a burden. The local software development manager was out of ideas as well. I started my investigation one evening. The first thing I looked at was their code coverage. Not stellar at 76% but not so bad either. I scratched my head and dug into the source code and started looking at the tests. And I didn’t have to dig deeper to find the problem: the tests were crap. I remember a small test that alone got 40% coverage! It was a dirty hybrid of unit and integration test that tested a high level event processing method with the right parameters. It didn’t even check what would happen when one of the parameters is missing or has the wrong value.

In their defense, they had assigned a “junior developer” to write the tests while the “senior guys” wrote actual code. How did we fix it? We didn’t ask the team to increase code coverage, in fact, we didn’t even mention it. We started educating them on how to write good unit tests. We encouraged them to watch videos during office hours etc. After initial resistance and passive-aggressiveness, they saw the light and realized that a lot of errors Q/A were discovering, they could find themselves using proper unit tests techniques. More importantly, they realized that for them to professionally grow, they must learn to write proper tests and write themselves. The bug count went down significantly.

The Google approach

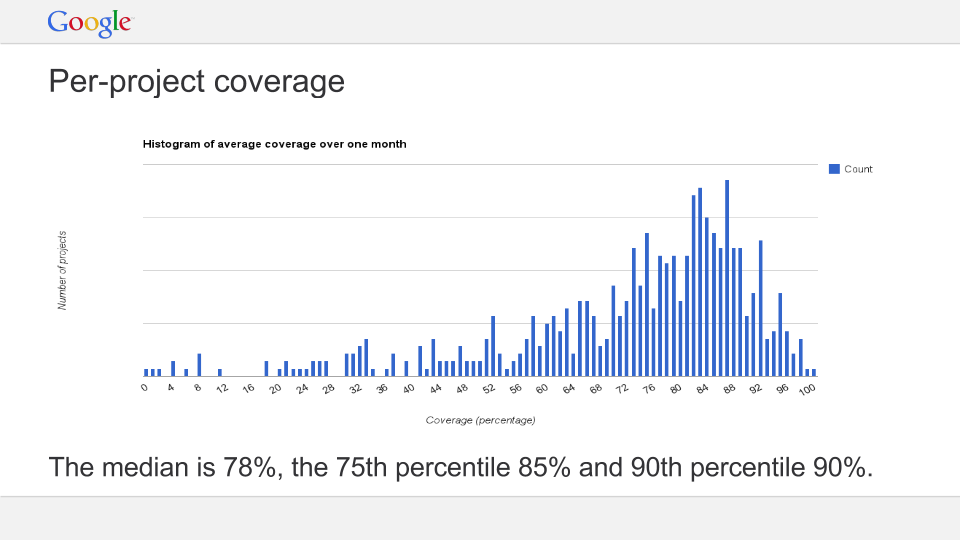

I like the Google approach. They strive for 85% code coverage but it is not “set in stone”. Their code coverage results over a month are shown in the graph below.

Pretty Impressive.

Summary

Managers should expect their team to have high coverage but they must not turn it into a target. Metrics do not make good code. The ultimate goal is to have fewer bugs that escape into the production.