Previously, I talked about the ill-fated rewrite of our core product. The ‘second system’, although better and faster than its predecessor, was rejected by the customer. But the story has a silver lining - one thing that we got right in the process that empowered us to grow and thrive: we built a highly productive remote development team.

In this post, I’ll share my experiences: how through trial and error (and with luck), we finally got the right formula and made it work for us.

Part of the original system team was one of the best duct-tape developers I’ve ever worked with. We called him ‘The Code Machine’. He didn’t write clean code, but he wrote it fast as hell and made sure it worked. The original system, done with a gun to our heads, was a big, complex, monolith application and the boundaries between its modules were ill defined. Computer scientists refer to this type of code as tightly-coupled and the system is referred to as non-orthogonal.

The ‘second system’ had a more grand vision and we needed to grow the team to build it right and on schedule. We hired another developer, a bright, young CS graduate to work on the system. One problem with the original system quickly became evident to me: because the code was tightly-coupled (the auto-generated UML class diagrams resembled a spider’s cobweb), the new developer couldn’t work independently: changing one part of the system indirectly impacted other parts. While they were not bickering, the two developers couldn’t get out of each other’s way and the progress was slow. Parallel to all this, the upper management decided to give ‘remote software development’ a try. Someone on the board recommended a company from Hyderabad, India and before I even knew it, I was interviewing a bunch of remote Java developers.

The non-orthogonality problem was further magnified when the remote developer joined the team. Because the system was tightly-coupled, he was going to have to learn it all before he could become productive. Somehow, we isolated a few ‘modules’ so that he could start writing features without spending months learning the entire system. But his changes frequently conflicted with the work of the local team and integration became a nightmare, requiring everyone’s involvement. This issue aside, I had other concerns as well. It appeared that the remote developer was just ‘covering his ass’ and leaving a paper trail. I hate bureaucracy and don’t work that way. I later learned, that the offshore company had a ‘different’ culture than the one I was trying to build.

Let me stop here to summarize the situation: we had a complex system with huge overlap of module responsibilities. Changes rippled through the whole system and affected the entire team. We had a remote developer in India, outside of our comfort (time)zone, and integration often forced everyone to work odd hours. To make matters worse, the remote developer had low morale and the offshore company we were contracting with, was ripe with dysfunctional politics.

It was then that I decided to slow ourselves down and think about how can we avoid all this in the new design. Since we didn’t have a dedicated Q/A, I assigned that responsibility temporarily to the new developer so he could be productive (it was dick move, but he was allowed time to learn and practice his coding skills and he ended up getting SCJP during that period). The remote developer got re-assigned to a new R&D project that the CEO was cooking up.

When the things calmed down, we realized that three things must happen if we want to scale our development:

- The new system must be orthogonal. It should be modular and modules should communicate with other only using well defined messages, the public API. I wanted the modules to be 100% blackbox so they could be developed and tested independently… abstractions that do not leak.

- Each module must be assigned to a single developer or a team who will 100% own it. I wanted to get around the Brook’s Law by minimizing communication between local and remote developers as much as possible.

- We must do something about the culture and fix the working conditions for our remote developers. We needed the right people who would take full ownership.

1. Building Orthogonal System

In two-dimensional geometry, two lines are orthogonal if they intersect each other at right angles. This affords a kind of independence, where you could move along one of the lines without affecting your position projected onto the other line. This simply means that in an orthogonal system, you could easily change the ‘networking layer’ without affecting the ‘database layer’ or the ‘UI layer’. In Pragmatic Programmer, Andrew and David used an excellent analogy to describe a non-orthogonal system:

You’re on a helicopter tour of the Grand Canyon when the pilot, who made the obvious mistake of eating fish for lunch, suddenly groans and faints. Fortunately, he left you hovering 100 feet above the ground. You rationalize that the collective pitch lever controls overall lift, so lowering it slightly will start a gentle descent to the ground. However, when you try it, you discover that life isn’t that simple. The helicopter’s nose drops, and you start to spiral down to the left. Suddenly you discover that you’re flying a system where every control input has secondary effects. Lower the left-hand lever and you need to add compensating backward movement to the right-hand stick and push the right pedal. But then each of these changes affects all of the other controls again. Suddenly you’re juggling an unbelievably complex system, where every change impacts all the other inputs. Your workload is phenomenal: your hands and feet are constantly moving, trying to balance all the interacting forces.

Helicopter controls are decidedly not orthogonal.

We took the layered approach to system design similar to the OSI model. The layers we built had following qualities:

- Each layer had a single major responsibility.

- Layers exposed a well-defined API. Communication with other layers was done only using the API.

- Layers (with the exception of business logic) communicated with only one other layer.

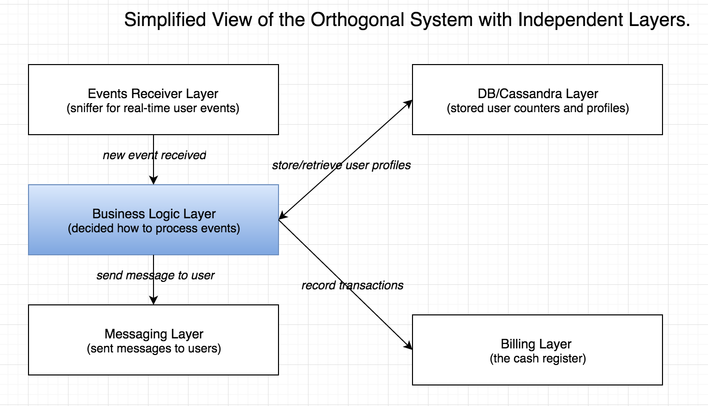

Here’s what the design of the design looked like:

In addition to the layers, there were several smaller subsystems not shown in the diagram above such as the ‘Admin UI’ tool and simulators for testing the system end-to-end.

2. Circumventing Brook’s Law

Brook’s Law sucks. It basically says that the communication overhead increases as the number of people involved in a project increases. Communication with the remote team that is outside +/- 5 hours of your timezone becomes a burden. We had full 12 hours time difference. So we decided to extend the principal of single responsibility to developers and decided that each layer shall have a single owner or a small sub-team located in the same timezone. Initially, I was little hesitant silos that might affect team work and create local optimums, but we had a great team and it never became an issue. The upper management was concerned about ‘individual owners getting hit by a bus’ and wanted some level of duplicity. To achieve that, we decided that we’ll keep the system as simple as possible, perform regular code reviews and document it well. Our approach to documentation was simple:

- For every layer or module, I came up with a high-level product document. The goal was to describe the what and why (not how) in simple and concise terms. The document had a vision that described what the module would do in one sentence and why we were building it, a 10,000 foot overview, core requirements and a list of the things that the module shall not do.

- The developers created design documents. They were a brief description of how the project was organized into sub-packages, followed by interaction diagrams. On average, this document was mostly 3-6 diagrams with very little text.

The documentation was kept in the GitHub wiki along with the source code.

So we had divided the system in a manner that individual pieces could be assigned independently to remote teams and the instructions were clear enough to minimize communication. We wanted to assign ownership and get out of their way. But there was a big problem: our remote developer wasn’t motivated enough to take ownership. Growing the team over there was out of the question since we had no control over the environment or the culture.

3. Getting the Right People On the Bus

As the remote developer was finally starting to become somewhat productive, I had concerns about his morale. I reached the conclusion that the things cannot be improved and we terminated the contract.

I was so disheartened at the state of remote software development that I was ready to write it off, but a fellow CTO for a different company told me that they’re getting great results on oDesk. I tried to experiment a little and asked for $1500/month budget that was approved. I found an independent consultant and contracted him on a part-time basis to work on our web admin tool. The guy was a winner. Whenever I assigned him a new task, he asked questions until he fully understood. He would then go away and send me regular updates on the progress. His releases were on time and his code was pristine. He didn’t program in Java, but luckily had (equally smart) friends who did. It’s a long story but he helped us grow the team and we hired four full time developers and he eventually setup his own office to provide them a space to work from.

I visited the remote team once or twice a year. These visits helped me understand the issues these guys faced and the face-to-face whiteboard meetings enabled them to understand more complex designs easily.

Summary

I purposely told the story of how my company built a remote software development team instead of giving recommendations up front in the hope that you would draw your own conclusions. In retrospect, we went through trial and error and luckily found the right people that made it work. But despite all of that, it was a strenuous journey. If the remote developers require constant babysitting and you cannot measure their productivity, it’s probably not working. If you could afford it, steer clear of remote developers working +/- 3 hours outside of your time zone. If you decide to take the offshore route, here are the key takeaways from our experience:

- Divide the system into independent layers and minimize the overlap between the layers. Keep the number of layers that have to communicate with one another to a minimum.

- Go to extreme lengths to hire the right people; avoid offshore sweatshops or hired guns. Understand that it will require extra time and effort to make them productive. When you find the right people, treat them with the same respect as you would extend to local developers, make them feel like they are part of the family, and make sure they are being compensated fairly. Don’t make them stay up late nights to attend meetings. For example, instead of making four guys stay up late to talk to me, I would schedule the weekly meeting during my evening, their morning.

- Provide clear requirements. I cannot stress this enough. Be as concise and as crystal clear as possible. If the requirements aren’t clear, the remote developers might get blocked waiting for answers or even worse, deviate from the requirements and build something entirely different.