Books / Programming Language Design / Chapter 10

Interpreters

Interpreters are a type of programming language implementation in which a program (the interpreter) creates an in-memory (data structure) representation of the program, and executes the program by traversing this data structure.

As we saw in chapter 5 and chapter 6, the results of parsing can be represented as a parse tree. We also saw how if we are careful about arranging the source language’s grammar rules, we can ensure that the structure of the parse tree encodes semantic information about the input string of tokens (i.e., the program.) This makes parse trees a very appropriate choice of data structure to use when implementing an interpreter.

Abstract syntax trees (ASTs) are also a common choice of data structure for interpreters. An AST “pares down” the parse tree and simplifies its structure so that semantic constructs — things like operators, functions, function calls, etc. — are represented is as straightforward a way as possible. However, there is no truly fundamental difference between an AST and a parse tree.

Recursive evaluation

One of the simplest ways to implement an interpreter is via recursive evaluation of the program’s tree representation. Here’s the basic idea. There is a function called the evaluator that takes a reference to a tree node as a parameter and returns a value as a result. The tree node represents the program (or partial program) to execute, and the value returned represents the result of the computation. In Java, this function might look something like this:

Value evaluate(Node expr) {

...

}The evaluator looks at the type of node it is evaluating, and then carries out the computation specified by that node. For some types of nodes, carrying out the computation may be fairly simple. For example:

- If the node is a literal value, just return that value

- If the node is a variable reference, look up the value of that variable and return it

For nodes with a more complex structure, recursive evaluation can be necessary. For example, consider the expression

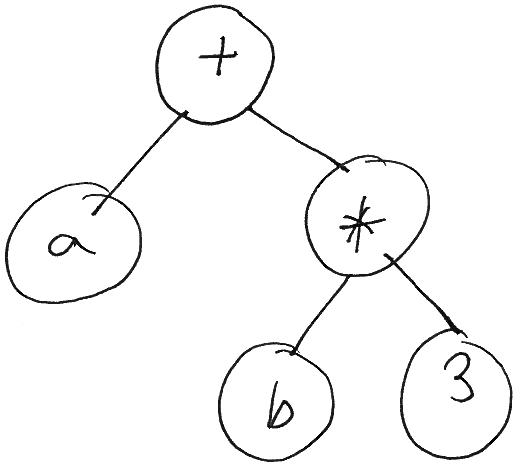

a + b * 3

This expression might be represented as the following tree:

Note that the + node is multiplying the results of evaluating the subexpressions a and b * 3. So, before the product can be computed, the values of the subexpressions must be computed.

The beauty of recursive evaluation is that evaluating the results of subexpressions simply requires a recursive call to the evaluator! Here is how the evaluate method might handle the constructs in the example tree shown above:

Value evaluate(Node expr) {

Value left, right;

switch (expr.getSymbol()) {

case INT_LITERAL:

return expr.getIntegerValue();

case IDENTIFIER:

return lookupVariable(expr.getIdentifer());

case PLUS:

left = evaluate(expr.getLeftChild());

right = evaluate(expr.getRightChild());

return computeSum(left, right);

case TIMES:

left = evaluate(expr.getLeftChild());

right = evaluate(expr.getRightChild());

return computeProduct(left, right);

default:

throw new EvaluationException("Unknown node type: " + expr.getSymbol());

}

}There are some method calls that aren’t fully explained in this code, but their meaning should be reasonably apparent from context. For example, expr.getLeftChild() would get the left (first) child of a expr.

Tradeoffs of recursive evaluation

Recursive evaluation has positive and negative features.

The benefit of recursive evaluation is that it is very simple to implement. A tree-based interpreter based on recursive evaluation can be fully implemented in very little time, even for a complete programming language.

The drawback of recursive evaluation is that the performance will generally be significantly below native code executing on the CPU. A slowdown of 10x to 100x compared to native code is typical.

So, interpreters based on recursive evaluation are good for prototyping new languages (where speed of implementation is important), and also for applications that don’t require hardware-level execution speed.

Interestingly, in many real-world situations, programs are more likely to be I/O-bound (meaning that the majority of program execution time is spent waiting for input and output operations to complete) rather than CPU-bound. For such programs, the slowdown of recursive evaluation may not be significant. This is one reason why languages such as Ruby and Python, whose primary implementation is based on recursive evaluation, are widely used in production systems.

Other interpretation strategies

Recursive evaluation is not the only possible approach to implementing an interpreter. Another common approach is bytecode compilation, where the source program is translated into a series of bytecode instructions, and then the interpreter executes the bytecode instructions. This strategy can result in performance closer to native machine code, at the cost of making the interpreter more complex.