Books / Patterns for Beginning Programmers / Chapter 24

Neighborhoods

The subarrays pattern, discussed in Chapter 23, considers some problems in which calculations need to be performed on only some of the elements of an array. The solution in that chapter is appropriate only for problems in which the subarray is defined using an offset and a length. This chapter again considers situations in which calculations need to be performed on only some of the elements, but those elements are now conceptualized as a neighborhood around a particular element.

Motivation

To blur a discretized audio track or visual image, you must calculate the (weighted) average of the elements that are in the neighborhood of a particular element. For an array (which might, for example, contain a sequence of amplitude measurements of an audio track), such neighborhoods have an odd number of elements and are centered on the element of interest. Such a neighborhood is illustrated in Figure 20.1.

Figure 20.1. A Neighborhood of Size 3 around Element 4

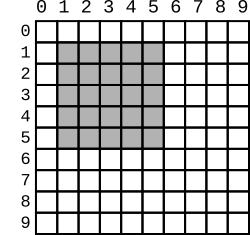

For an array of arrays (which might, for example, contain the color values of the pixels in an image), such neighborhoods are square with an odd number of elements, and are centered around the element of interest. Such a neighborhood is illustrated in Figure 20.2.

Figure 20.2. A 5x5 Neighborhood around Element (3,3)

Review

If you were to use the subarrays pattern from Chapter

23,

you would describe the subset of the elements in Figure

20.1 using an offset of 3 and a length

of 3. Similarly, you would describe the subset of the elements in

Figure 20.2 using a roffset (row offset)

of 1, a coffset (column offset) of 1, a rlength (row length) of

5, and a clength (column length) of 5. While there would be

nothing technically wrong with this solution, it is not consistent with

the conceptual notion of a neighborhood around an element. In other

words, it is not consistent with the way domain experts think about the

problem.

Thinking About The Problem

When domain experts think about the blurring problem, they think about calculating the weighted average of the elements that are near a center element. Exactly what this means differs with the domain and the dimensionality of the data.

For an array (e.g., a sequence of amplitude measurements from a discretized sound wave), each element is identified by a single index. So, you need one value to represent the center of the neighborhood and one (odd) value to represent the size of the neighborhood.

For a rectangular array of arrays (e.g., a raster/grid of color measurements), each element is identified by two indexes, commonly called the row index and column index. So, you need two integer values to represent the center of the neighborhood. Then, if you limit yourself to square neighborhoods (as is common), the size of the neighborhood can be represented by a single (odd) integer.

The Pattern

As in the subarray pattern of Chapter

23,

you need to add formal parameters to the signature of the method you are

concerned with. Methods that are passed an array will have two

additional parameters (the index and the size), and methods that are

passed an array of arrays will have three additional parameters (the

row index, col index, and size).

Also as in the subarrays pattern, you need to calculate the bounds on

the loop control variables. While this was quite simple for subarrays,

for neighborhoods it’s a little more complicated. Returning to Figure

20.1 and Figure

20.2, you can see that you want to have the

same number of elements on both sides of the center element. Using

integer division, this means that you want to have size/2 elements on

both sides of the center element.

For an array, this means that the lower bound will be given by

index - size/2 and the upper bound will be given by index + size/2.

For an array of arrays, this means that the lower bound for the rows

will be given by row - size/2, the upper bound for the rows will be

given by row + size/2, the lower bound for the columns will be given

by col - size/2, and the upper bound for the columns will be given by

col + size/2.

Of course, as always, care must be taken about whether to use a weak

inequality or a strong inequality. In this case, a weak inequality is

needed to ensure the elements on the boundary are included in the

neighborhood. To see why, first consider the array in Figure

20.1. In this example, index is 4 and

size is 3. So, size/2 is 1, meaning that the bounds are 4 - 1

(i.e., 3) and 4 + 1 (i.e., 5).

Examples

As always, it’s instructive to consider some examples.

Some Obvious Examples

One way to implement the blurring operations discussed in the introduction of this chapter is to use an accumulator (as in Chapter 16) to calculate a neighborhood average. For an array (e.g., a sampled audio clip), this can be implemented as follows:

public double naverage(double[] data, int index, int size) {

double total;

int start, stop;

start = index - size / 2;

stop = index + size / 2; // Equivalently: stop = start + size - 1

total = 0.0;

for (int i = start; i <= stop; i++) {

total += data[i];

}

return total / (double) size;

}

For an array of arrays (e.g., a raster representation of an image), this can be implemented as follows:

public double naverage(double[][] data, int row, int col, int size) {

double total;

int cstart, cstop, rstart, rstop;

rstart = row - size / 2;

rstop = row + size / 2;

cstart = col - size / 2;

cstop = col + size / 2;

total = 0.0;

for (int r = rstart; r <= rstop; r++) {

for (int c = cstart; c <= cstop; c++) {

total += data[r][c];

}

}

return total / (double) (size * size);

}

A Less Obvious Example

You might also need to use a “plus-sign-shaped neighborhood” in which

only the elements in the row or column of the center element are

included. You could, use an if statement to include only the

appropriate elements. Alternatively, you could use two loops, one that

iterates over the elements with the same row and one that iterates over

the elements that have the same column, as follows:

public double paverage(double[][] data, int row, int col, int size) {

double total;

int count, cstart, cstop, rstart, rstop;

rstart = row - size / 2;

rstop = row + size / 2;

cstart = col - size / 2;

cstop = col + size / 2;

total = 0.0;

count = 0;

for (int r = rstart; r <= rstop; r++) {

total += data[r][col];

++count;

}

for (int c = cstart; c <= cstop; c++) {

total += data[row][c];

++count;

}

// Eliminate the double counting

total -= data[row][col];

--count;

return total / (double) count;

}

Finally, you could use an array (or array of arrays) of indicators, as

discussed in Chapter

8,

to control which elements are included. The shape and size of the

indicator array (or array of arrays) would correspond to the shape and

size of the neighborhood. Indexes to be included in the calculation

would have an indicator of 1 and indexes to be excluded would have an

indicator of 0. The indicator would then be multiplied by the

calculation. Regardless of the approach, you have to correctly count the

elements that are in the total.

Using the Subarray Pattern

Obviously, the neighborhoods pattern and the subarray pattern are closely related, even though they differ conceptually and in the particular parameters that are used. Hence, one can easily combine them. For example, the method for calculating the neighborhood average could use the method for calculating the total of a subarray, rather than duplicate that code, as follows:

public double naverage(double[] data, int index, int size) {

double sum;

int offset;

offset = index - size / 2;

sum = total(data, offset, size);

return sum / (double) size;

}

There is one important subtlety here that you shouldn’t ignore. The intervals in the neighborhood pattern are closed whereas the intervals in the subarray pattern are half open (i.e., open on the right).

A Warning

As with the subarray pattern of Chapter 23, the invoker can pass invalid parameters. Hence, you should validate these parameters and respond to invalid values appropriately (either by throwing an exception or using valid default values).