The concept of the minimum viable product or the MVP was popularized by Eric Reis in his book The Lean Startup. He defines it as:

The minimum viable product is that version of a new product which allows a team to collect the maximum amount of validated learning about customers with the least effort.

Startups fail for many reasons but one of the biggest reasons is that they build products that their customers do not want. By that time, it’s too late. They have already spent months or even years of their lives building a great product - a grand vision - that the market isn’t, unfortunately, willing to purchase. MVP is a strategy to avoid exactly that scenario: building something that the customers do not want.

Eric cites the story of Zappos. They didn’t start out with a grand vision of building a cool website, distribution and call centers. Nope. Zappos started by testing a simple hypothesis: are customers willing to buy shoes online?

They went to local shoe store, took pictures of each of their products and put them online. If anyone bought shoes from them [at this early stage], they planned to go to the store, buy the shoes and mail them to the customer. There was no big business behind it; there was a website and a hope that they’ll get so many orders that it will get annoying to do all the purchasing and shipping manually. It was all to test their big idea.

MVP is a great way to test the actual usage and assumptions as opposed to conventional market research that includes researching online, surveys etc. which often provide misleading results.

Software teams can learn a lot from MVP and apply it to build products that meet their client needs. When I first heard of MVP, I thought of it as a rebranding of ‘Continuous Delivery (CD)’ which, along with the practices of incremental and iterative development, has been around for a long time. But there is a huge difference and it lies in how software developers understand and perceive these concepts. This article captures the definition I hear from most developers when I ask them about incremental development:

In incremental model the whole requirement is divided into various builds … more easily managed modules. Each module passes through the requirements design, implementation and testing phases. A working version of software is produced during the first module, so you have working software early on during the software life cycle. Each subsequent release of the module adds function to the previous release. The process continues till the complete system is achieved.

The article even has an illustration showing how the Mona Lisa would be built incrementally or piece-by-piece:

The problem is that “working software early on in the life cycle” doesn’t happen in real-life. Modules take up a lot of time; developers start arguing about technologies and methodologies, various architectures and database systems are evaluated and the complete painting takes up a long time. When it gets released, the customer turns around and demands that Mona Lisa’s dress should be of red color instead of deep forest green!

Traditional methodologies guide the software development process to ensure that the product gets built right, but the MVP answers the bigger question: are we building the right product? While Agile does promote evolutionary development where results are demonstrated to stakeholders after each iteration, a MVP isn’t just show and tell. It is a real product that gets released to the users. Software teams could build a MVP using Agile/Scrum, incrementally and deliver it continuously.

Because a MVP gets released to the customers, it requires support from the organization, clients and other departments. Building a MVP isn’t easy. On the one hand, you want to limit it to few essential or key features, but on the other hand, you want to deliver something that your customers will find useful so they can start using it. You must find the right balance.

Releasing the product only when it is almost or absolutely ready is a mistake I have seen far too often. Usual software development goes like this: software teams talk to their clients and stakeholders to get their requirements (Everyone does that. Right?). They create a product vision (or write functional specifications) and show it to the stakeholders. Once the stakeholders agree on the requirements and the product vision, the team set out to build the product. The product is divided into several layers or several subs-systems, if following SOA or microservices architecture. Each layer is built piece-by-piece, incrementally and iteratively. Even the CI/CD pipeline is there since week one. Finally, when everything is ready, the product is ‘released’ to the customer. Then the customer flips and ask for changes or new features. It happens almost always. Depending on how well the team captured and modeled their requirements, the rework could take weeks or months!

I made this mistake when I architected a telecommunications project using Service Oriented Architecture (SOA). While the team followed iterative approach to individual services and did continuos integration, we didn’t implement the front-end that our customer could use and provide feedback on early on. We used Agile and it worked great for the database layer, the business layer, the sniffers, the messaging layers and the load balancers. When the product was complete, we released it to our big client for a pilot with few thousand users. That same week, I received a phone call from the CEO asking for very different functionality, in an apologetic tone. It turned out that once the client used the product, they changed their mind. The big release date was one or two months away and we had to do major rework to adopt the change.

What can we learn from this story? Build the MVP. While I’m not against refactoring and adopting to change, in this case, we could have avoided extra effort if we had built a MVP. We didn’t built in a vacuum. We prototyped but prototypes only help so much. In the example I gave, the product’s goal was to support mobile menus that allowed people to send messages and transfer funds. We prototyped and mocked the menus in Balsamiq and even went as far as creating a simple HTML page that allowed the client to interact with the menu options. At regular intervals, we’d send client videos of partial functionality in action. But prototypes and videos aren’t remotely as interesting as the actual product. Clients looked at those and said everything looks great. But once they got the actual product on their phones, they got creative and came up with new ideas. If I were doing the project all over again, the first thing I’d do is build the front-end (menus), use a simple database (even SQLite instead of Cassandra) and make the product work on real devices and give it to the client. Plumbing to make it work across multiple sites and NoSQL databases would come later.

A little while ago, I was working on a backend with REST based microservices architecture. There were several clients with different needs and there was a lot of unknown. A common complaint from the developers who worked on earlier projects was that the clients always change their minds after the release which makes their products messy since they accrue technical debt. I had a Déjà vu. So we figured out the most urgent needs and defined a milestone that would deliver a working product. It’ll have fewer services than our grand vision, but everything will work end-to-end. It won’t be perfect or complete, but it will have just the right functionality they need to get up and running and provide us the feedback. And we will grow and evolve it over time.

The closest reference to MVP I could find in software development is a concept called ‘Tracer Bullets’ that was first used by Andy and Dave in their book the The Pragmatic Programmer:

We once undertook a complex client-server database marketing project … The servers were a range of relational and specialized databases. The client GUI, written in Object Pascal, used a set of C libraries to provide an interface to the servers … There were many unknowns and many different environments, and no one was too sure how the GUI should behave.

This was a great opportunity to use tracer code. We developed the framework for the front end, libraries for representing the queries, and a structure for converting a stored query into a database-specific query. Then we put it all together and checked that it worked. For that initial build, all we could do was submit a query that listed all the rows in a table, but it proved that the UI could talk to the libraries, the libraries could serialize and unserialize a query, and the server could generate SQL from the result. Over the following months we gradually fleshed out this basic structure, adding new functionality by augmenting each component of the tracer code in parallel.

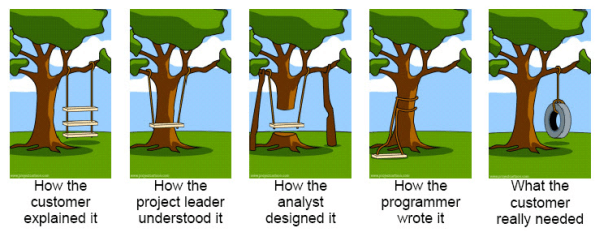

So when you are setting out on a journey to build a new product and have lots of unknowns and assumptions, build a MVP - or use Tracer Bullets. Make sure to build the right thing. You might have seen this image a thousand times already, but this is exactly what MVP will avoid:

Notes

John Mayo-Smith illustrates two approaches to building a pyramid:

-

Build it gayer by layer

-

Start with a smaller pyramid and keep growing it. Just like MVP. Delivering a “smaller product” that captures essential features that the customer could actually use and deliver feedback on.