Books / Ruby for Beginners / Chapter 36

Subtyping vs Inheritance

Comparing to modules, there is a better way “to specify a new implementation while maintaining the same behaviors …, to reuse code and to … extend original software…”. We’re not using inheritance mechanism to copy over variables and methods from one object to another, but about the actual sub-typing.

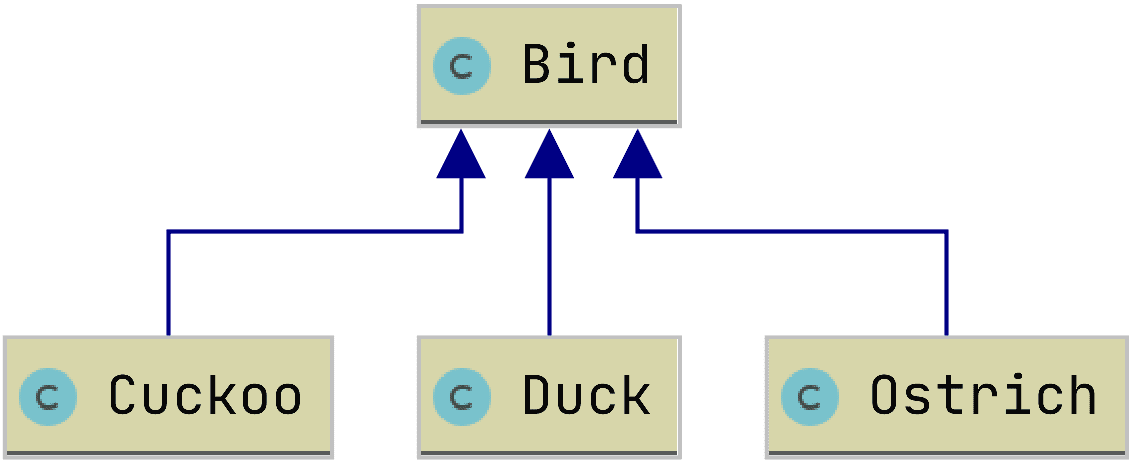

For example, duck, cuckoo and ostrich are subtypes of a bird:

For the definition of word “inherit” from Oxford dictionary we already mentioned in the previous chapters, the diagram above makes perfect sense:

Derive (a quality, characteristic, or predisposition) genetically from one’s parents or ancestors.

Even based on our life experience we can say that yes, subtypes are correct, and the abstraction above makes sense. And this fact enables polymorphism: it doesn’t really matter what kind of bird it is, we can feed the bird, let it fly, and so on.

From technical standpoint, in Ruby language subtyping is inheritance, and it is what it should be. Look at the code with empty classes:

class Bird

end

class Cuckoo < Bird

end

class Duck < Bird

end

class Ostrich < Bird

end

In statically-typed languages like C# (or Java, Golang) we can introduce “interface” instead of the inheritance:

interface Bird {

void Feed();

void GiveWater();

}

interface Duck : Bird {

}

interface Cuckoo : Bird {

}

interface Ostrich : Bird {

}

And one of the things that is no code for interface, only method definition (or “interface definition”). You can’t just mindlessly copy a code over. But in dynamically-typed languages like Ruby, we keep interfaces either in mind, or introduce some abstract class (“Bird” above), and use inheritance.

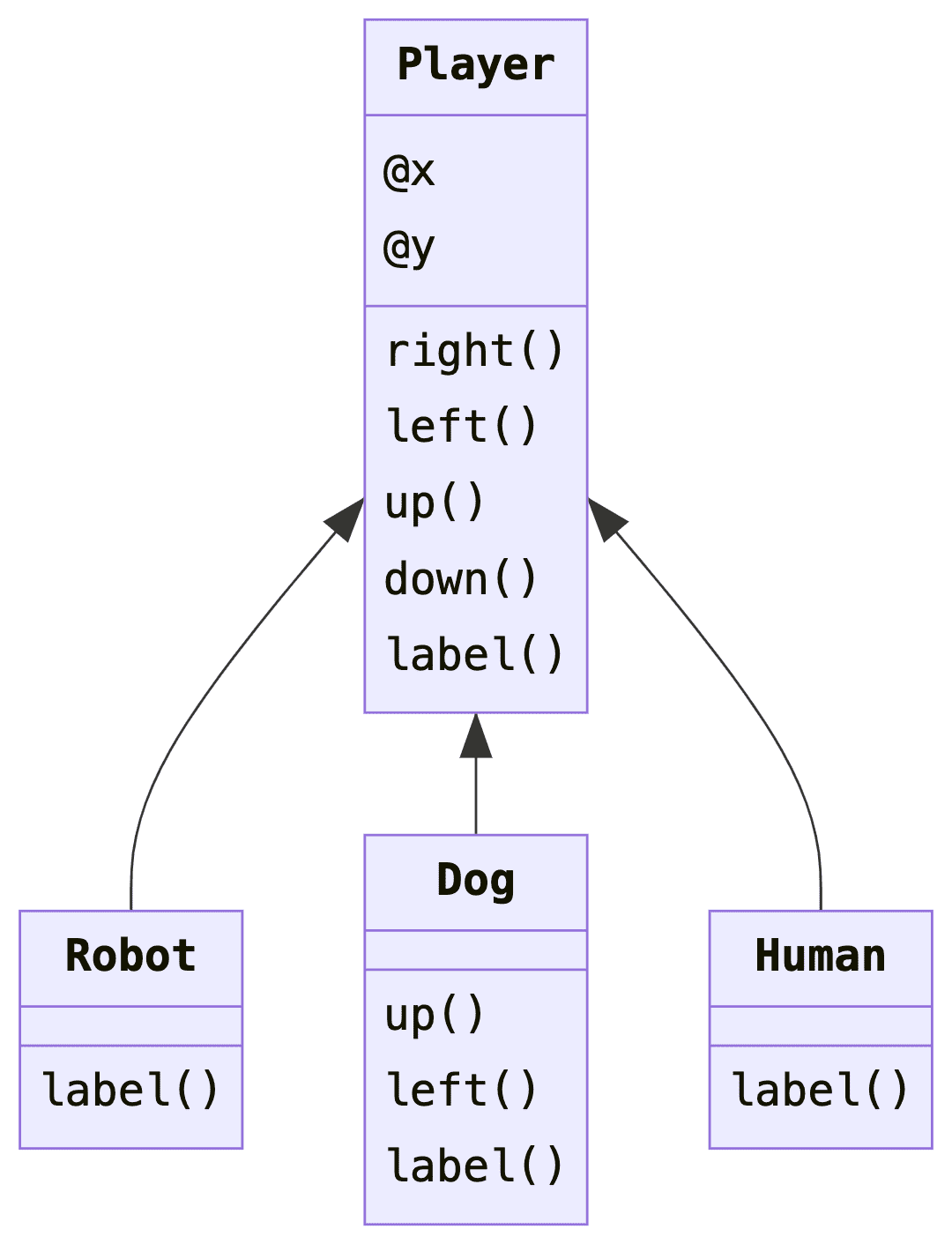

We can use similar approach for the program with human, robot, and dog. Instead of modules, introduce some abstract class that is not represented in real life, like “Player”. And then inherit from this class all these entities, like:

The approach looks very similar to modules. However, in this case we’re saying that explicitly: “we see abstraction, it’s some sort of a player”. No matter what happens to a player, it always has left, right, up, down, label methods. Any method that accepts Dog, Human, or Robot can assume these methods exist. We also extract entities like Dog, Human, and Robot and letting others know that they’re somewhat different. They have something similar, but we do not inherit Human from Robot, like it was before. These five methods are the only interface.

Exercise Stop right here and before we implement the diagram above together, try to implement it yourself! You should have all the knowledge now, can you do it? Practice, practice, practice!

The code would look like:

class Player

attr_accessor :x, :y

def initialize(options={})

@x = options[:x] || 0

@y = options[:y] || 0

end

def right

self.x += 1

end

def left

self.x -= 1

end

def up

self.y += 1

end

def down

self.y -= 1

end

def label

end

end

class Robot < Player

def label

'*'

end

end

class Dog < Player

def up

end

def left

end

def label

'@'

end

end

class Human < Player

def label

'H'

end

end

We used subtyping through inheritance to extract the common functionality. And unfortunately or fortunately, Ruby language has no interfaces, so we cannot code the “classic subtyping” and extract interface.

Ruby is very flexible language and brings freedom to a developer: whatever you do is up to you. There are numerous ways of extracting abstraction. Moreover, Ruby will even let you to create abstract “Player” class we defined above. It’s because we don’t have a definition of abstract classes in Ruby, but it should be one in your head. Nothing prevents a programmer from messing up Dog, Human, and Robot classes by adding whole bunch of unrelated methods that would spoil the common interface.

It is probably not a big deal when program isn’t lengthy. However, imagine your first day in a corporation. Pat created “Player” class and submitted changes to git repository. You’re looking at commit history and it says that the file “player.rb” was added to the repo 5 years ago. Pat works for a different company now. How would you know about the intent here? Is it okay, 5 years later to create an instance of “Player” class?

In other words, the freedom comes with a price. It’s very easy to write a code that you can understand, but not that easy so everyone else will understand it 5 years later without a problem. If a class is abstract, it’s probably worth adding a comment or extra check to it.

It’s always up to developer how to use inheritance, what’s going to be an abstract class, are you going to reuse the code with modules, and so on. If you’re unsure, don’t make it smart, make it simple. Making simple is often harder than making it smart though. In this case use modules, add comments, and document everything.