Books / Ruby for Beginners / Chapter 42

Ruby Version Manager (RVM)

Information in this chapter is very important for a Ruby beginner. Probably it would worth to keep it at the beginning of the book. However, it can take some time to digest the information about RVM, and our focus was on a quick start. Now when you know how Ruby works and (hopefully) did a lot of exercise, you can exercise with setting up some useful tools.

RVM is a thin layer for your shell (which is “bash”, but hopefully Oh-My-Zsh) or IDE. Every programmer often runs Ruby app with “ruby app.rb”, but where the actual “ruby” comes from? Let’s look at the “which” command output when RVM isn’t installed:

$ which ruby

/usr/bin/ruby

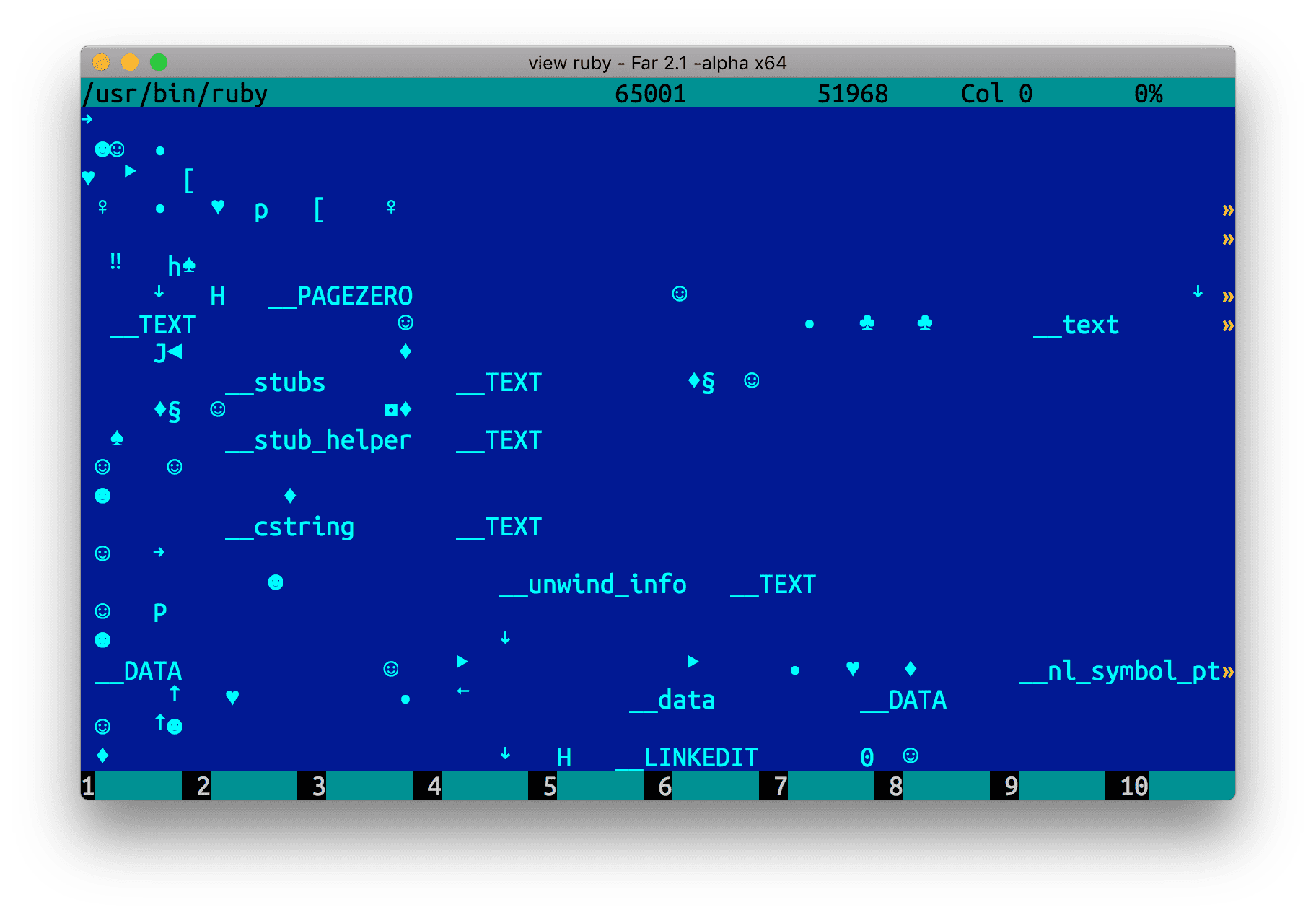

So Ruby programming language is just a binary executable file located at “/usr/bin/ruby”. Here is how it looks like when you open this file with Far Manager:

If you delete the file, you won’t be able to run Ruby programs. But how does the shell know that Ruby needs to be started from “/usr/bin” directory? Look at the $PATH environment variable for your shell (your output can be slightly different):

$ echo $PATH

/usr/local/bin:/usr/bin:/bin:/usr/sbin:/sbin

So $PATH variable has multiple directories, separated by “:” (colon):

/usr/local/bin/usr/bin(where “ruby” is actually located)/bin/usr/sbin/sbin

When you type “ruby” command, your shell tries to find the file in the first directory. If the file wasn’t found, it iterates over the next directories until the file is found. One can redefine this variable such a way, so shell looks up the file somewhere else first (you’re getting it right, you need to prepend new directory to the $PATH, not to append). But where you should do that?

All shells (bash, zsh, etc) keep its settings in home directory. You can find out what’s your home directory by typing “echo $HOME” or “echo ~”. Bash keeps settings in “.bashrc” dot-file in home directory.

In POSIX/UNIX-compatible systems (not on Windows) “Dot-file” is a file prefixed with dot, and “hidden” by default. It’s not visible with “ls” command, but visible with “ls -a” (“list all”). Dot-files in Windows aren’t hidden, and visibility is controlled by so-called file attributes. There is Ctrl+A combination in Far Manager to control this attribute on Windows (for Far Manager on POSIX/UNIX-compatible systems this dialog is slightly different).

Zsh settings can be found at home directory in “.zshrc” file (full path is “~/.zshrc”). $PATH environment variable almost always defined in dot-files that keep settings for your shell.

But why do we need RVM and all of that jazz?

We already know that Ruby is a standalone program located somewhere on your disk. But what if new version is released? The fact is that releases are happening quite often, and new versions have new features, improved performance, and so on. We were talking about Ruby language, but what was the actual language on your system? You can get the version banner with the following shell command:

$ ruby -v

ruby 2.6.1p33 (2019-01-30 revision 66950) [x86_64-darwin16]

“System” Ruby is the “ruby” located in your “/usr/bin” directory and ships with your operating system.

However, it’s not the case for Windows, and the latest news for the macOS 10.15 say:

Scripting language runtimes such as Python, Ruby, and Perl are included in macOS for compatibility with legacy software. Future versions of macOS won’t include scripting language runtimes by default, and might require you to install additional packages. If your software depends on scripting languages, it’s recommended that you bundle the runtime within the app.

Moreover, system Ruby often isn’t the latest Ruby released, there is probably newer version with new features and performance improvements. But how do you know that’s the latest version?

Hold on for a moment, you probably won’t like the latest-latest Ruby. It doesn’t mean that new versions are always bad. The very latest versions are almost always “nightly builds”. All changes that were introduced during the day go the single branch and get built automatically.

Side note: compilation is translation of the source into machine language. Programs written with Ruby language don’t get compiled, but interpreted: we run Ruby programs with “ruby app.rb”, not just “./app”. So there is no such a thing as build for Ruby programs. However, lots of programmers do refer to “build” as to successful run of all the tests, sometimes with some magic to additional assets like images, CSS files, and so on. But the Ruby itself is written with C. As could be seen if you call “show-method loop” in Pry (you might need to install pry-doc with “gem install pry-doc”):

$ pry

[1] pry(main)> show-method loop

From: vm_eval.c (C Method):

Owner: Kernel

Visibility: private

Number of lines: 6

static VALUE

rb_f_loop(VALUE self)

{

RETURN_SIZED_ENUMERATOR(self, 0, 0, rb_f_loop_size);

return rb_rescue2(loop_i, (VALUE)0, loop_stop, (VALUE)0, rb_eStopIteration, (VALUE)0);

}

So the nightly builds for Ruby language itself actually exist. But for Ruby programs programmers often refer to “build” as to successful execution of all the tests with some extra magic.

For the record, popular Firefox browser is available as nightly builds. Here is what nightly build is, according to Firefox developers:

Every day, Mozilla developers write code that is merged into a common code repository (mozilla-central) and every day that code is compiled so as to create a pre-release version of Firefox based on this code for testing purposes, this is what we call a Nightly build. Once this code matures, it is merged into stabilization repositories (Beta and Dev Edition) where that code will be polished until we reach a level of quality that allows us to ship a new final version of Firefox to hundreds of millions of people.

In addition, there are also “preview” builds. The difference between nightly and preview is that the latter is more stable. But what we’re really interested in is “stable” or “LTS” build. In other words, there are different kinds of builds:

- nightly build

- preview

- alpha

- beta

- stable

- LTS (long-term support) - not really a build, more like a version tag

To find out what’s the latest stable is, go to official Ruby language downloads and scroll down a bit to see “Stable releases section”. You can download it right from the website. It comes as “tar.gz” archive, use the following command to unpack it:

$ tar xzf ~/Downloads/ruby-X.Y.Z.tar.gz

Don’t forget to change “X.Y.Z” to the Ruby version you’ve downloaded. After unpacking this file you’ll see directory with the source code. You can “cd ruby-X.Y.Z” and “ls -lah” to see contents. You can’t run the source code, so you need to build the Ruby so you have executable “ruby” file. You can do it with running “./configure” and “make”:

$ cd ruby-X.Y.Z

$ ./configure

checking for ruby... /usr/bin/ruby

tool/config.guess already exists

tool/config.sub already exists

checking build system type... x86_64-apple-darwin17.6.0

checking host system type... x86_64-apple-darwin17.6.0

checking target system type... x86_64-apple-darwin17.6.0

checking for clang... clang

checking for gcc... (cached) clang

...

$ make

CC = clang

LD = ld

...

At the end you’ll end up with “ruby” file in your current directory. You can run the file to check the version:

$ ./ruby -v

ruby 2.5.1p57 (2018-03-29 revision 63029) [x86_64-darwin17]

Prefix “./” says that the file needs to be executed from the current directory, not from the file located in one of the $PATH directories. Compare the following with what’s written above:

$ ruby -v

ruby 2.3.3p222 (2016-11-21 revision 56859) [universal.x86_64-darwin17]

If you do “sudo make install”, you’ll replace your system Ruby with newly compiled version. However, on macOS it will probably end up in “/usr/local/bin”, while the system Ruby is in “/usr/bin”. It shouldn’t be a problem, because “/usr/local/bin” goes before “/usr/bin” in $PATH.

You might need to restart the terminal, or “source ~/.bashrc”, “source ~/.zshrc”, depending on your shell.

Would you agree that all of that was somewhat complicated? Why the Ruby team did things this way? The answer is that there is only one Ruby, but many operating systems. Not only Windows, macOS, Linux, but also different versions of these operating systems. Every operating system has its own settings, related to performance, for example. So Ruby can take advantage of these settings, one need to build Ruby on exactly the same computer that you have (or on your own). Also, CPUs can differ for the same operating system. And one CPU optimization can work on one computer, but won’t work on another. For example, when one computer is newer, and another is older.

We’ve built Ruby language, replaced the system Ruby with newer version, and we won’t have to go through all of that again. Great! Hold on a second, there is one more thing. It’s not always that easy in software development world (and it’s why we’re getting paid a lot as programmers).

You have probably already noticed that version is represented by three numbers. Not the Ruby 1, 10, 42. But Ruby 2.3.3, Ruby 2.5.1, and so on. Why do we need three numbers instead of just one?

There is such thing as Semantic Versioning (or SemVer). The summary says:

Given a version number MAJOR.MINOR.PATCH, increment the:

- MAJOR version when you make incompatible API changes,

- MINOR version when you add functionality in a backwards compatible manner, and

- PATCH version when you make backwards compatible bug fixes. Additional labels for pre-release and build metadata are available as extensions to the MAJOR.MINOR.PATCH format.

For Ruby 2.3.1, the major is 2, the minor is 3, and the patch is 1. We’ll look closer into this, because it is important.

Software development process can include:

- bug fixes - patch version is increasing

- adding features and improvements, minor version is increasing

- breaking (not compatible with previous release) changes were introduced, major version is increasing

While we fixing bugs, the program logic mostly stays the same. Two versions may differ, but not that much. Two versions of Ruby would have one or more bug fixes. You can drop-in replace one version with another and everything will work exactly the same way. Developers increase patch number because they want to emphasize that new version is better, it has more fixes.

Let’s say we had version “0.1.0” (recommended initial version in SemVer), and new version is “0.1.1”. It means something was fixed, and “0.1.1” is better. Or, for example, we had version “0.1.9”, and the new one is “0.1.10”. Something was fixed in “0.1.9”, and patch number was increased by 1. In fact, you can replace “0.1.10” with “0.1.0”, and nothing serious should happen (except unfixed bugs, of course).

While improving functionality or introducing features, old versions do not have this functionality or features. What does it mean for Ruby?

Say, new version has “yeah” operator that prints “Oh, yeah!”. We use this new feature to create a program that works. But for some reason we roll back to the previous version. But the old Ruby doesn’t implement “yeah” and our program won’t work, we’re get—ting error now!

So to let others know that this version is new, and you can’t roll back, we increase the minor version (the number in the middle), and at the same time we drop the patch number to zero. For example, an app version will increase from “0.1.10” to “0.2.0”. New version will increase all the patches from the previous one. Since new version has new features, minor number was increased by 1.

If you look at Ruby, versions 2.3.3 and 2.5.1 differ by 2 minor releases. It means that we had 2.4.x, and later on some new features we release in 2.5.x. If you write a program that uses 2.5.x-specific language features, it won’t work on versions below this number, like 2.4.x, 2.3.x and so on.

Major version can be increased in the following cases:

- When software is ready for production, major version can be increased from 0 to 1.

- When breaking changes have been introduced, the version can be increased from 1 or above by 1.

Often developers say that this change “breaks backwards compatibility”: programs written with new Ruby most likely won’t work while executed with the previous version.

But that’s the worst case. When major version of Ruby is released, we often have instructions on how to upgrade already existing software to the new Ruby.

This raises some philosophical aspects of software development, especially when it comes to computer languages or frameworks. What would be your long-term release strategy?

- Would you go fast, break things, and don’t look back?

- Or would you be more conservative, support old versions, because there is plenty of already existing code out there, and nobody is going to rewrite it only because new language/framework has been released?

Many development teams try to find the balance. They’re open about what versions are maintained, which versions are LTS (have long-term support), which versions are EOL (end of life), which versions are in security maintenance phase (have only security bug fixes). Anyway, Ruby doesn’t stay still, companies have to upgrade their Ruby versions. Nobody wants to deal with EOL Ruby version, because it’s much easier to upgrade gradually over the time, step by step. And that’s why we, as programmers, are getting paid to do these upgrades (and our unit tests here come into play and help us a lot).

We’ve figured out the source of issues related to the Ruby language growing and getting more fun and performant. And businesses have reasonable questions: “okay, Ruby language exists in multiple versions. Some projects can be upgraded to the latest, some require more time and money. But the system Ruby is always the same! What would we do if we have two projects? One project requires new version, and another requires older Ruby. What if these two projects need to talk to each other (micro-service architecture), and we need to keep it running on the same computer?”

Solution to the problem is quite simple and little bit smart: we’ll create directories where we’ll keep all Ruby versions:

- 2.5.1

- 2.3.3

- 2.0.0

and so on. Every Ruby binary is going to be named as “ruby-2.5.1”, “ruby-2.3.3”, and so on. Instead of running “ruby app.rb”, we’ll be running “ruby-2.5.1 app.rb”. It’s that simple. But there is one more thing…

Besides “ruby”, there is also “gem” binary (type “which gem” to locate the binary, for system Ruby it should be in “/usr/bin/gem”). We use “gem” to install “gems” (libraries) available at RubyGems that were written by people like you and me from around the world. Being downloaded, these files live somewhere on your local filesystem.

Every gem has a parameter called “required_ruby_version”. So if you installed a gem for 2.5.1, there is a chance that this gem won’t work for 2.3.3. So along with directories for rubies, somehow we need to create directories for gems as well. Turns out that it’s impossible to have multiple Ruby versions?

It is possible. If we continued to experiment, we would find the way to keep multiple rubies on our filesystem, and all them would work seamlessly without a hassle. As you can imagine, this problem already existed a long time ago, when developers realized they need multiple rubies, and some way to switch between them. This is how Ruby Version Manager (RVM) was born.

RVM is not unique, the similar concepts with slightly different variations exist for other languages as well. There is NVM for Node.js, Node Version Manager. We’ll look closer into RVM, but the fundamentals are the same.

Installation. Instructions are available at RVM website and short summary explains what it is:

RVM is a command-line tool which allows you to easily install, manage, and work with multiple ruby environments from interpreters to sets of gems.

You need to run these two commands to install RVM:

$ gpg --keyserver hkp://keys.gnupg.net --recv-keys 409B6B1796C275462A1703113804BB82D39DC0E3 7D2BAF1CF37B13E2069D6956105BD0E739499BDB

$ \curl -sSL https://get.rvm.io | bash -s stable

Installation log says:

Installing RVM to /Users/ro/.rvm/

Adding rvm PATH line … /Users/ro/.bashrc /Users/ro/.zshrc.

Adding rvm loading line to ... /Users/ro/.bash_profile /Users/ro/.zlogin.

Installation of RVM in /Users/ro/.rvm/ is almost complete:

* To start using RVM you need to run `source /Users/ro/.rvm/scripts/rvm`

in all your open shell windows, in rare cases you need to reopen all shell windows.

It recommends to run “source /Users/ro/.rvm/scripts/rvm” (your path is probably different) if you want to use RVM right now without restarting a terminal. Now we can run RVM to see its version:

$ rvm -v

rvm 1.29.4 (latest) by Michal Papis, Piotr Kuczynski, Wayne E. Seguin [https://rvm.io]

Or help:

$ rvm --help

Usage:

rvm [--debug][--trace][--nice] <command> <options>

for example:

rvm list # list installed interpreters

rvm list known # list available interpreters

rvm install <version> # install ruby interpreter

rvm use <version> # switch to specified ruby interpreter

rvm remove <version> # remove ruby interpreter

rvm get <version> # upgrade rvm: stable, master

...

RVM installer modified $PATH variable we mentioned above, and installed itself into “~/.rvm” directory (you can see what’s inside with “ls -lah ~/.rvm”). RVM has hijacked the $PATH, prefixing it with its own directories, and will feed you this or another Ruby language depending on certain circumstances. What what exactly are those circumstances that define which Ruby version is going to be used at the moment?

Here is the magic of RVM comes into play, and some people don’t like RVM because of this magic. RVM will replace the “cd” (change directory) command of your shell. When you change a directory, RVM tries to detect which Ruby needs to be used right now. The detection algorithm is rather simple and explained below, but RVM has two options when directory gets changed:

- Silently (or almost silently) feed you the right Ruby version so you won’t notice anything.

- Don’t do anything.

But how does RVM know what version do you need, what’s the logic? It is quite simple. There is convention in Ruby community that Ruby version for a project should be specified in “.ruby-version” dot-file right in the root directory of a project. This file has the semantic version, like “2.5.1”. When you change directories, RVM will read up this file, and will change the current version to the version that is needed. If the Ruby version hasn’t been downloaded yet, RVM will notify you, and show the command you need to run to download this specific Ruby version.

Why won’t we experiment with RVM? We’ll create test directory, write down “.ruby-version” file, then change directory to the parent and change into this directory again - you need this for RVM to trigger things. Because initially there won’t be any “.ruby-version” file. But before we do that, look at the current Ruby version:

$ ruby -v

ruby 2.5.1p57 (2018-03-29 revision 63029) [x86_64-darwin17]

$ which ruby

/usr/local/bin/ruby

Now we can test the RVM magic:

$ mkdir rvm-test # create rvm-test

$ cd rvm-test # switch to rvm-test

$ echo "2.3.1" > .ruby-version # write down 2.3.1 to the file

$ cd .. # go to the parent directory

$ cd rvm-test # and back

Required ruby-2.3.1 is not installed.

To install do: 'rvm install "ruby-2.3.1"'

It worked! RVM said “ruby-2.3.1” isn’t installed, and suggested a command to install (other commands are available with “rvm --help”).

Let’s give it a try and run the command. RVM tries to find precompiled binary for your operating system:

Searching for binary rubies, this might take some time.

No binary rubies available for: osx/10.13/x86_64/ruby-2.3.1.

If file was not found, the source code will be downloaded from the official Ruby website and will get compiled on your computer - the same way we did before manually! So RVM is just a set of handy scripts, and it’s much easier to use than reinventing the wheel and do it yourself with “./configure” and “make”.

When everything’s done, we can check the version to make sure it’s installed and works:

$ ruby -v

ruby 2.3.1p112 (2016-04-26 revision 54768) [x86_64-darwin17]

$ which ruby

/Users/ro/.rvm/rubies/ruby-2.3.1/bin/ruby

These manipulations allowed RVM to override the default Ruby with the Ruby specified in “.ruby-version”:

Before:

- Version: “

ruby 2.5.1p57” - Path: “

/usr/local/bin/ruby”

After:

- Version: “

ruby 2.3.1p112” - Path: “

/Users/ro/.rvm/rubies/ruby-2.3.1/bin/ruby”

Keep in mind that the old file “/usr/local/bin/ruby” still exists, we just modified environment variables. And all of that was done automatically, while changing directory (“cd”).

As you might already noticed, having “.ruby-version” is crucial for RVM and similar tools to work without issues. This also allows to avoid questions in a team, like “Which Ruby version should I use for the project?”, everyone knows where to look. It’s convention and a good practice.

We’ve installed specific Ruby version knowing how RVM internals work. But can you install and use a Ruby language binary of specific version without that trick with creating the file? Yes, it’s possible. There are few commands available:

- “

rvm list known” - shows the list of rubies available to install. We need MRI (Matz’s Ruby Interpreter) releases. - “

rvm install ...” - install specific version of Ruby runtime.

$ rvm install 2.5.1

Searching for binary rubies, this might take some time.

No binary rubies available for: osx/10.12/x86_64/ruby-2.5.1.

Continuing with compilation. Please read 'rvm help mount' to get more information on binary rubies.

...

We’re installing Ruby 2.5.1 above. Debugging info says that there is no precompiled binary for our operating system and we’re about to download and compile from the source code.

RVM did the search for Ruby based on the following features:

osx- type of the operating system, “osx” for macOS (legacy name for macOS), Linux, Windows, and so on.10.12- version of operating system.x86_64- CPU architecture.ruby-2.5.1- Ruby version.

If you multiply the number of supported operating systems by the number of different versions for these operating systems, then by the number of CPU architectures, and then by the number of Ruby versions you’ll get the number of Ruby binaries that RVM needs to keep on its servers.

But why there is a need for that? Downloading Ruby binary takes seconds, while compilation takes much more time and less eco-friendly. Imagine how many computers need to consume electricity for a significant amount of time to get exactly the same binary! This could be optimized, and thanks to RVM for keeping at least some of the Ruby binaries.

From a “consumer” perspective, we don’t need to know too much about these details. What we wanted to do is to understand how to install and use RVM without a dot-file. We know how to install certain version of Ruby (“rvm install 2.5.1”), but how do we use it?

Imagine we have multiple versions: 1, 2, 3. If there is no any “.ruby-version” in current directory, somehow we need to pick the version we want to use. For that purpose we have RVM “use” sub-command, with a clear syntax:

$ rvm use 2.5.1

Using /Users/ro/.rvm/gems/ruby-2.5.1

$ ruby -v

ruby 2.5.1p57 (2018-03-29 revision 63029) [x86_64-darwin16]

$ rvm use 2.3.1

Using /Users/ro/.rvm/gems/ruby-2.3.1

$ ruby -v

ruby 2.3.1p112 (2016-04-26 revision 54768) [x86_64-darwin16]

To see all the rubies installed in your system use “list” sub-command, like:

$ rvm list

ruby-2.3.1 [ x86_64 ]

ruby-2.4.2 [ x86_64 ]

* ruby-2.5.0 [ x86_64 ]

=> ruby-2.5.1 [ x86_64 ]

# => - current

# =* - current && default

# * - default

RVM also has “default” version concept. In other words, the version that you currently prefer when no configuration is specified. You can enable default version with the following commands:

$ rvm alias create default 2.5.1

Creating alias default for ruby-2.5.1.....

$ rvm use default

Using /Users/ro/.rvm/gems/ruby-2.5.1

You can now “rvm use default” to use 2.5.1. You can create as many aliases as you want. In practice you probably won’t need to use this feature very often.

Our quick introduction to RVM is over. You might hear the definition “gemset” in some docs or while talking to your team. It’s not used that often at the moment, because latest versions of Bundler solved the problem RVM gemsets used to solve in the past. But so you know, gemsets are sets of gems, RVM allows you to keep the certain set of gems for the same Ruby version.

You don’t need to remember all the RVM settings, but knowing how it works is always useful. Without that knowledge RVM looks magical, but it’s a standard practice today. There are some other tools for other languages:

- NVM - Node.js version manager

- VirtualEnv - the similar version manager, but for Python

- Version managers for Golang, Elixir, Java, and so on.

Software developers often deal with multiple languages at the same project. For example, Ruby programmers often use JavaScript and Golang. Setting up multiple versions managers takes time, let alone you need to remember command line options for each of them. Fortunately, there is an open source tool (with GPL-compatible license) that lets you to manage multiple runtime versions with a single command line-interface! The tool is asdf-vm and has more than 50 plugins for programming languages and other environments.